Director: Ian David Diaz

Writer: Ian David Diaz

Producers: Ian David Diaz, Angela Banfill

Cast: Oliver Young, Richard Banks, Giles Ward

Country: UK

Year of release: 1996

Reviewed from: VHS tape

In 1999, a low-budget British thriller called The Killing Zone was released straight to VHS. Directed by Ian David Diaz, it was produced by ‘The Seventh Twelfth Collective’, which was Diaz, Julian Boote and their pals, The same gang made ultra-obscure horror anthology Dead Room (only ever released in Greece and Thailand!), Anglo-Canadian horror Fallen Angels and two American thrillers, Bad Day and Darkly Dreaming Billy Ward.

It’s a lo-o-ong, long time since I’ve seen The Killing Room, but a little digging reveals that it is about a cool, calm underworld assassin named Matthew Palmer. Viewing the world from behind large, thick-framed glasses, Palmer’s name is a tip of the hat to Harry of that ilk and there are other Michael Caine references scattered throughout the three stories which together make up the 65-minute feature.

The first story concerns a couple of small-time crooks who are believed to have stolen some cocaine. Tied to chairs in a warehouse, they are interrogated by a sadistic gangster while Palmer stands implacably by. This story is a remake of a short film which Diaz shot in 1996 called The Interrogation.

The point of all this is that, 20 years on, I found The Interrogation among a pile of VHS tapes I was taking to the skip so decided to give it one last watch before it becomes landfill. It’s a smartly-directed, tightly written, generally well-acted little thriller. Much of the film is experienced crook Fenton (Richard Banks) and first-timer Finn (Oliver Young) tied up and questioned by ‘Mad Dog’ McCann (Giles Ward), a tall, pony-tailed, dinner-jacketed sadist who wants to get this all over and done with so he can make it to a dinner party on time.

Fenton takes his impending death in his stride. Finn is scared shitless. Both are adamant that the contacts they were due to meet were already dead – and without any cocaine – when they got there. McCann doesn’t believe them. While McCann knocks the two around and reveals how much homework he has done on them – he knows their motives, their backgrounds, their needs – Palmer just stands motionless in the background in trench coat and spoddy glasses. But he’s not window dressing, he will become very relevant towards the end of the story.

The reason why all this is of interest to me is the casting. Banks, Young and Ward all reprised their roles when the film was remade as part of The Killing Zone, which starred Padraig Casey as Palmer. But in this short film, Martin Palmer is played by none other than Kevin Howarth.

Kevin’s page on the Inaccurate Movie Database lists his first film as a thriller called Cash in Hand, then relationship drama The Big Swap, both listed as ‘1998’ along with Razor Blade Smile. In fact The Big Swap was his debut, filmed in 1996, followed by RBS then Cash in Hand (filmed as The Find). So this short apparently just predates The Big Swap. By the time that Diaz was shooting the feature version, Kevin already had several films on his CV and either didn’t need to do The Killing Zone or was simply too busy.

Subsequently of course Kevin has become a familiar face to fans of British horror with roles in The Last Horror Movie, Summer Scars, Cold and Dark, Gallowwalkers and The Seasoning House.

If I hadn’t know this was Kevin Howarth, I probably wouldn’t have recognised him. Maybe it’s just the hair, glasses and make-up but he looks somewhat rounder of face, less gaunt than he appears in later films. Once he speaks, however, the voice is unmistakable. Kevin has always been particularly good at portraying largely emotionless characters (much harder than it sounds) and Palmer is about as emotionless as they come. But he’s threatening, in the same way that a gun on a table is threatening.

Although most of the cast of this film disappeared after making this and Dead Room, a few names in the credits have, like young Mr Howarth, gone on to greater things. Co-producer and editor Piotr Szkopiak is now an experienced soap editor, with many episodes of EastEnders, Emmerdale and Corrie to his name. And composer Guy (son of Cliff) Michelmore is now – how cool is this? – the regular composer for animated Marvel projects, including series based on Thor, Hulk, Avengers, Dr Strange and Iron Man.

It’s not quite true to say that there’s no record of The Interrogation anywhere as it has a page on the BFI website, but that’s all. So now it has a review too. It’s a crisply directed, enjoyable short but, unless Ian David Diaz decides to post it online, your chances of ever seeing it are effectively nil. On the other hand, a DVD of The Killing Zone can be picked up easily and cheaply so the story’s there if you want to check it out. Just not with Kevin Howarth.

MJS rating: B+

MJ Simpson presents: the longest-running single-author film site on the web, est.2002.

Pages

▼

Wednesday, 27 July 2016

Thursday, 21 July 2016

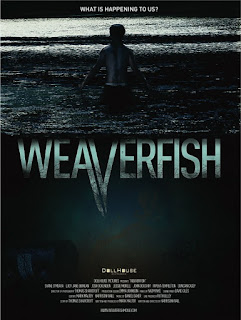

Weaverfish

Director: Harrison Wall

Writers: Harrison Wall, Mark Maltby

Producer: Mark Maltby

Cast: Shane O’Meara, Lucy-Jane Quinlan, Ripeka Templeton

Country: UK

Year of release: 2013

Website: www.weaverfishmovie.co.uk

Weaverfish is a pleasant surprise. It is largely unknown, probably because it has only been released as VOD, and its basic premise is hardly inspiring. A group of horny teenagers go somewhere remote to spend the night partying, drinking, smoking and perhaps getting lucky. Many, many horror films have started out that way and the vast majority of them have turned out to be awful.

The secret lies in the characters. Normally the young people in these films are just awful. Self-entitled millennials or sweary, lary chavs. In far too many films the viewer can identify with no-one on screen and basically wants them all to die as soon (and as painfully) as possible.

The six main characters in Weaverfish are all believable and mostly sympathetic. Reece (Shane O’Meara: Waterloo Road) is a sensitive, introspective guy with a camera around his neck. He takes a bit of persuading to let his hair down and party, but he’s up for a drink when offered so he’s not some stick-up-the-arse buzzkill. Matt (Josh Ockenden: The Underwater Realm, Arthur and Merlin) was his best mate at school although they’re not quite as close now. Matt can be a bit of a prick but he’s not a bad lad. He is dating the very cute Charlotte (Lucy-Jane Quinlan: The Cutting Room) for whom Reece has long carried a torch. Quinlan gives a particularly fine performance, balancing Charlotte on a fine line between vulnerability and resilience.

Abi (Jessie Morrell) is Charlotte’s blousy pal. Shannon (Ripeka Templeton) is Reece’s younger sister who is more keen on partying than her brother. Rounding up the sextet is Mike (John Doughty: The Hounds) a slightly older guy with white dreadlocks who is in a band. He could potentially be an arsehole but actually comes across, once we get to know him, like the others, as a rounded, believable, sympathetic character. All of these are people you could quite happily spend some time with. None of them ever do anything inexcusably dumb.

Do you see, other film-makers? It is possible.

The set-up is that there is an area of water, Fountainhead Creek, which has been sealed off both landwards and riverwards since a small child went missing there several years earlier. There is a disused oil refinery behind the fence. Mike and his bandmate Chris (Dusty Rhodes) – who is either bi or just uses that as a way of getting laid – have discovered a gap in the fence across the mouth of the creek through which they squeeze a small inflatable, twice. As well as those mentioned, there are four or five other teenagers, plus plenty of booze, a few pills, some tents and some music equipment.

Among a litany of strong points, Weaverfish’s big weakness is that we spend a long, long time getting to know the characters. They are well-defined, both in themselves and their relationships, but we signed up for a horror movie not a teen drama. The 95-minute film is nearly halfway through before anything unnerving happens, by which time it’s the morning after the night before and people are waking up. There’s a great deal of puking, but that can be put down to last night’s pills and Pilsner – or can it? When half the group disappear along with the boat, presumably ferried back to the town by Chris, the poorly state of Abi and Shannon persuades the remaining six to set off across land, hoping to find a stretch of fence with a road alongside which might allow them to contact someone who can alert the police and call an ambulance. (There is the traditional, brief hold-up-the-phone-got-no-signal scene.)

As it happens, these six are the most clearly developed characters from the original dozen but we didn’t know that until now so we’ve been trying to become familiar with more characters than we needed to. A shorter first act, with fewer secondary characters, would definitely have benefitted the film. It’s good that we have got to know these characters so well and can fully sympathise and empathise with them. It’s good that we can see the Matt/Charlotte relationship coming apart as he surreptitiously targets Shannon, and that we can see that Charlotte really should be with Reese (plus we can see a relationship developing between Abi and Mike). But Act One could have been tightened up without losing that, I think.

As it happens, these six are the most clearly developed characters from the original dozen but we didn’t know that until now so we’ve been trying to become familiar with more characters than we needed to. A shorter first act, with fewer secondary characters, would definitely have benefitted the film. It’s good that we have got to know these characters so well and can fully sympathise and empathise with them. It’s good that we can see the Matt/Charlotte relationship coming apart as he surreptitiously targets Shannon, and that we can see that Charlotte really should be with Reese (plus we can see a relationship developing between Abi and Mike). But Act One could have been tightened up without losing that, I think.

So, the problem they face is that Shannon and Abi, as well as feeling sick, have each developed a large patch of distorted skin on their torsos. An attempt to clean this results in a quite startling and disturbing effects shot which is really where the horror kicks in. Once Mike and Matt also admit to having this symptom, it becomes clear that it has been caused by yesterday afternoon’s dip in the creek, which Reece and Charlotte both passed up. Something from that old oil refinery is still floating about in the water, and it’s not good. (Someone comments that they’ve seen no fish. There is also a complete absence of ducks, swans, gulls, herons or any other sort of aquatic wildlife.)

Comparatively little actually happens in the second act, apart from the group moving forward and people feeling worse, so it is tremendously to the credit of film-makers Harrison Wall and Mark Matlby – and their talented cast – that we remain gripped as the film inches inexorably into horror territory before finally tipping over into a full-on sci-fi conspiracy thriller in the short third act. Commendably, the film ends at exactly the right point, a denouement which is both enjoyably bleak and satisfyingly vague. The (partial) revelation of what is going on is utterly startling, but in a jaw-dropping way, not a jump-out-of-your-seat way.

Comparatively little actually happens in the second act, apart from the group moving forward and people feeling worse, so it is tremendously to the credit of film-makers Harrison Wall and Mark Matlby – and their talented cast – that we remain gripped as the film inches inexorably into horror territory before finally tipping over into a full-on sci-fi conspiracy thriller in the short third act. Commendably, the film ends at exactly the right point, a denouement which is both enjoyably bleak and satisfyingly vague. The (partial) revelation of what is going on is utterly startling, but in a jaw-dropping way, not a jump-out-of-your-seat way.

That’s actually another feather in the film’s cap; it never goes for a cat-scare or other cheap horror gags. Everything here is characterisation and narrative.

Wall and Maltby came out of university and went into TV post-production where they saved their salaries in order to fund this £10,000 production. Wall has done editorial gigs on the likes of Dickensian, Humans and Poirot, while Maltby has worked on The Fades, South Riding and Whitechapel. Wall previously directed two shorts on which Maltby provided special effects: sci-fi musical CyberBeat and a horror called The Snatching which has some similarities to Weaverfish. More recently, Maltby has worked as a colourist on features including Blood Moon, Howl and The Haunting of Radcliffe House. Their script was based on an idea (initially much more of an action/sci-fi story) by their friend Thomas Shawcroft who was DP on Weaverfish and whose various camera operator gigs have included Community, Doctor Who and Galavant (meaning he could potentially have worked with Weird Al!).

Shot near Southampton over 15 days in June 2011, the film premiered at the Bootleg Film Festival in Toronto in May 2012 where it picked up the Audience Award and Quinlan won Best Actor (Female). That version ran 100 minutes and although five of those have subsequently been cut, it could stand to lose another ten or so from that first act. There was a private UK screening for cast and crew the following month at the Prince Charles Cinema and the film also screened in Luxembourg in September that year as part of a 'British and Irish' season. Weaverfish was released in this country through Vimeo on Demand in October 2013 while Continuum Motion Pictures (whose other UK titles include Any Minute Now, Survivors and Bikini Girls vs Dinosaurs) handled the American VOD release in September 2014.

Shot near Southampton over 15 days in June 2011, the film premiered at the Bootleg Film Festival in Toronto in May 2012 where it picked up the Audience Award and Quinlan won Best Actor (Female). That version ran 100 minutes and although five of those have subsequently been cut, it could stand to lose another ten or so from that first act. There was a private UK screening for cast and crew the following month at the Prince Charles Cinema and the film also screened in Luxembourg in September that year as part of a 'British and Irish' season. Weaverfish was released in this country through Vimeo on Demand in October 2013 while Continuum Motion Pictures (whose other UK titles include Any Minute Now, Survivors and Bikini Girls vs Dinosaurs) handled the American VOD release in September 2014.

I was really genuinely impressed by Weaverfish. It’s not perfect but as a first feature from two young film-makers shot for tuppence ha’penny it’s a very fine piece of work indeed and a step above many comparable indie horrors. It has good casting and acting, good direction, good production values, good technical values and above all a fine script that prioritises characterisation over cheap exploitation. Well done, all involved. I hope this gets a proper DVD release so more people can discover it.

MJS rating: B+

Writers: Harrison Wall, Mark Maltby

Producer: Mark Maltby

Cast: Shane O’Meara, Lucy-Jane Quinlan, Ripeka Templeton

Country: UK

Year of release: 2013

Website: www.weaverfishmovie.co.uk

Weaverfish is a pleasant surprise. It is largely unknown, probably because it has only been released as VOD, and its basic premise is hardly inspiring. A group of horny teenagers go somewhere remote to spend the night partying, drinking, smoking and perhaps getting lucky. Many, many horror films have started out that way and the vast majority of them have turned out to be awful.

The secret lies in the characters. Normally the young people in these films are just awful. Self-entitled millennials or sweary, lary chavs. In far too many films the viewer can identify with no-one on screen and basically wants them all to die as soon (and as painfully) as possible.

The six main characters in Weaverfish are all believable and mostly sympathetic. Reece (Shane O’Meara: Waterloo Road) is a sensitive, introspective guy with a camera around his neck. He takes a bit of persuading to let his hair down and party, but he’s up for a drink when offered so he’s not some stick-up-the-arse buzzkill. Matt (Josh Ockenden: The Underwater Realm, Arthur and Merlin) was his best mate at school although they’re not quite as close now. Matt can be a bit of a prick but he’s not a bad lad. He is dating the very cute Charlotte (Lucy-Jane Quinlan: The Cutting Room) for whom Reece has long carried a torch. Quinlan gives a particularly fine performance, balancing Charlotte on a fine line between vulnerability and resilience.

Abi (Jessie Morrell) is Charlotte’s blousy pal. Shannon (Ripeka Templeton) is Reece’s younger sister who is more keen on partying than her brother. Rounding up the sextet is Mike (John Doughty: The Hounds) a slightly older guy with white dreadlocks who is in a band. He could potentially be an arsehole but actually comes across, once we get to know him, like the others, as a rounded, believable, sympathetic character. All of these are people you could quite happily spend some time with. None of them ever do anything inexcusably dumb.

Do you see, other film-makers? It is possible.

The set-up is that there is an area of water, Fountainhead Creek, which has been sealed off both landwards and riverwards since a small child went missing there several years earlier. There is a disused oil refinery behind the fence. Mike and his bandmate Chris (Dusty Rhodes) – who is either bi or just uses that as a way of getting laid – have discovered a gap in the fence across the mouth of the creek through which they squeeze a small inflatable, twice. As well as those mentioned, there are four or five other teenagers, plus plenty of booze, a few pills, some tents and some music equipment.

Among a litany of strong points, Weaverfish’s big weakness is that we spend a long, long time getting to know the characters. They are well-defined, both in themselves and their relationships, but we signed up for a horror movie not a teen drama. The 95-minute film is nearly halfway through before anything unnerving happens, by which time it’s the morning after the night before and people are waking up. There’s a great deal of puking, but that can be put down to last night’s pills and Pilsner – or can it? When half the group disappear along with the boat, presumably ferried back to the town by Chris, the poorly state of Abi and Shannon persuades the remaining six to set off across land, hoping to find a stretch of fence with a road alongside which might allow them to contact someone who can alert the police and call an ambulance. (There is the traditional, brief hold-up-the-phone-got-no-signal scene.)

As it happens, these six are the most clearly developed characters from the original dozen but we didn’t know that until now so we’ve been trying to become familiar with more characters than we needed to. A shorter first act, with fewer secondary characters, would definitely have benefitted the film. It’s good that we have got to know these characters so well and can fully sympathise and empathise with them. It’s good that we can see the Matt/Charlotte relationship coming apart as he surreptitiously targets Shannon, and that we can see that Charlotte really should be with Reese (plus we can see a relationship developing between Abi and Mike). But Act One could have been tightened up without losing that, I think.

As it happens, these six are the most clearly developed characters from the original dozen but we didn’t know that until now so we’ve been trying to become familiar with more characters than we needed to. A shorter first act, with fewer secondary characters, would definitely have benefitted the film. It’s good that we have got to know these characters so well and can fully sympathise and empathise with them. It’s good that we can see the Matt/Charlotte relationship coming apart as he surreptitiously targets Shannon, and that we can see that Charlotte really should be with Reese (plus we can see a relationship developing between Abi and Mike). But Act One could have been tightened up without losing that, I think.So, the problem they face is that Shannon and Abi, as well as feeling sick, have each developed a large patch of distorted skin on their torsos. An attempt to clean this results in a quite startling and disturbing effects shot which is really where the horror kicks in. Once Mike and Matt also admit to having this symptom, it becomes clear that it has been caused by yesterday afternoon’s dip in the creek, which Reece and Charlotte both passed up. Something from that old oil refinery is still floating about in the water, and it’s not good. (Someone comments that they’ve seen no fish. There is also a complete absence of ducks, swans, gulls, herons or any other sort of aquatic wildlife.)

Comparatively little actually happens in the second act, apart from the group moving forward and people feeling worse, so it is tremendously to the credit of film-makers Harrison Wall and Mark Matlby – and their talented cast – that we remain gripped as the film inches inexorably into horror territory before finally tipping over into a full-on sci-fi conspiracy thriller in the short third act. Commendably, the film ends at exactly the right point, a denouement which is both enjoyably bleak and satisfyingly vague. The (partial) revelation of what is going on is utterly startling, but in a jaw-dropping way, not a jump-out-of-your-seat way.

Comparatively little actually happens in the second act, apart from the group moving forward and people feeling worse, so it is tremendously to the credit of film-makers Harrison Wall and Mark Matlby – and their talented cast – that we remain gripped as the film inches inexorably into horror territory before finally tipping over into a full-on sci-fi conspiracy thriller in the short third act. Commendably, the film ends at exactly the right point, a denouement which is both enjoyably bleak and satisfyingly vague. The (partial) revelation of what is going on is utterly startling, but in a jaw-dropping way, not a jump-out-of-your-seat way.That’s actually another feather in the film’s cap; it never goes for a cat-scare or other cheap horror gags. Everything here is characterisation and narrative.

Wall and Maltby came out of university and went into TV post-production where they saved their salaries in order to fund this £10,000 production. Wall has done editorial gigs on the likes of Dickensian, Humans and Poirot, while Maltby has worked on The Fades, South Riding and Whitechapel. Wall previously directed two shorts on which Maltby provided special effects: sci-fi musical CyberBeat and a horror called The Snatching which has some similarities to Weaverfish. More recently, Maltby has worked as a colourist on features including Blood Moon, Howl and The Haunting of Radcliffe House. Their script was based on an idea (initially much more of an action/sci-fi story) by their friend Thomas Shawcroft who was DP on Weaverfish and whose various camera operator gigs have included Community, Doctor Who and Galavant (meaning he could potentially have worked with Weird Al!).

Shot near Southampton over 15 days in June 2011, the film premiered at the Bootleg Film Festival in Toronto in May 2012 where it picked up the Audience Award and Quinlan won Best Actor (Female). That version ran 100 minutes and although five of those have subsequently been cut, it could stand to lose another ten or so from that first act. There was a private UK screening for cast and crew the following month at the Prince Charles Cinema and the film also screened in Luxembourg in September that year as part of a 'British and Irish' season. Weaverfish was released in this country through Vimeo on Demand in October 2013 while Continuum Motion Pictures (whose other UK titles include Any Minute Now, Survivors and Bikini Girls vs Dinosaurs) handled the American VOD release in September 2014.

Shot near Southampton over 15 days in June 2011, the film premiered at the Bootleg Film Festival in Toronto in May 2012 where it picked up the Audience Award and Quinlan won Best Actor (Female). That version ran 100 minutes and although five of those have subsequently been cut, it could stand to lose another ten or so from that first act. There was a private UK screening for cast and crew the following month at the Prince Charles Cinema and the film also screened in Luxembourg in September that year as part of a 'British and Irish' season. Weaverfish was released in this country through Vimeo on Demand in October 2013 while Continuum Motion Pictures (whose other UK titles include Any Minute Now, Survivors and Bikini Girls vs Dinosaurs) handled the American VOD release in September 2014.I was really genuinely impressed by Weaverfish. It’s not perfect but as a first feature from two young film-makers shot for tuppence ha’penny it’s a very fine piece of work indeed and a step above many comparable indie horrors. It has good casting and acting, good direction, good production values, good technical values and above all a fine script that prioritises characterisation over cheap exploitation. Well done, all involved. I hope this gets a proper DVD release so more people can discover it.

MJS rating: B+

Saturday, 16 July 2016

Gallowwalkers

Director: Andrew Goth

Writers: Andrew Goth, Joanne Reay

Producers: Brandon Burrows, Courtney Lauren Penn

Cast: Wesley Snipes, Kevin Howarth, Riley Smith

Country: UK/USA

Year of release: 2013 (eventually…)

Reviewed from: UK DVD

Gallowwalkers does not come with a good reputation. Eleven per cent on Rotten Tomatoes. Average 3.6/10 on IMDB. Average 2.5 stars on Amazon. Most people who have expressed an opinion on it seemed to have been pretty negative. Received opinion is that the film is a clunker.

Well, I’m here to fly in the face of received opinion. I’ve watched Gallowwalkers and while even I hesitate to say it’s great, nevertheless it has undeniable elements of greatness. It also has undeniable flaws – what those are and why they exist I’ll come to in due course – but they are more than compensated for by the film’s positive aspects. I enjoyed it enormously.

Bear in mind that I also appreciated Andrew Goth and Joanne Reay’s previous film, Cold and Dark, which I described in Urban Terrors as “a curious but not unenjoyable melding of police procedural with weird horror.” That film has also been poorly regarded by most critics and punters. Maybe I’m just in tune with what these guys are trying to do.

Gallowwalkers has been described as a ‘zombie western’ but that’s misleading. Films like Cowboys and Zombies and Devil’s Crossing simply place a standard zombie scenario into a Wild West setting. Gallowwalkers is set in something approaching the 19th century American frontier and features characters who return to life, but there any similarities end. This isn’t just a horror film, certainly not just a western. It’s a mystical film, playing on the tropes of the more extreme end of the western genre, beyond Sergio Leone, beyond the old Django movies. Where some westerns are defined simply by iconography – Stetsons, six-shooters, steers and saloons – the real heart of the western genre lies in the themes it explores. Divorced from both the urban and the rural, divorced from both history and modernity, the best westerns are about isolation, struggle, identity, a quest for something undefined, perhaps even unreachable. Great westerns use the frontier of civilisation as a metaphor for the frontiers inside the protagonist’s mind and soul. All great westerns have a mystical element to them, however low it may be in the mix.

Occasionally a western comes along which ramps up the mystical element to eleven. The most famous example of that – and the most obvious comparison for Gallowwalkers, just in terms of its startling imagery and adamant non-realism – would be El Topo. Like Jodorowsky, Andrew Goth uses the western genre and some of its tropes to explore bigger, weirder, stranger ideas – just as he used the police procedural genre in Cold and Dark.

Does it always work? We’ll come to that.

So here’s the surprisingly straightforward plot, as eventually revealed through assorted flashbacks and revelations. Yer man Wesley Snipes is Aman (“a man” = everyman?), who swore revenge on the bastards who raped and murdered the girl he loved. He tracked them down to a jail and shot them in their cells but, in escaping, was himself shot by one of the jailers. His adopted mother called on the Devil to save her son and was granted her wish. But in returning Aman to life, the Devil decreed that those he killed would also return to life.

So those particular bastards are once again walking and talking, led by the thoroughly amoral Kansa (my old mate Kevin Howarth: The Last Horror Movie, The Seasoning House). Or at least, most of them are. Kansa doesn’t know how or why he and his men were reanimated, and hence he doesn’t know why his son wasn’t. Aman is on a quest to kill Kansa and his men, aiming to make sure they stay dead by ripping their fucking heads off. Kansa meanwhile is on a quest to find some mystical nuns whom he believes will be able to restore his son to life.

That’s it in a nutshell but there are all sorts of excursions to the plot, not all of which go anywhere in particular. What matters, more than the plot, are the individual scenes and the truly extraordinary imagery within those scenes. A combination of Goth’s direction, Goth and Reay’s screenplay, Henner Hofmann’s cinematography, Laurence Borman’s production design, Pierre Viening’s costumes and a make-up department overseen by the hugely experienced Jackie Fowler (with designs by the legendary Paul Hyett) – all of this creates a film for which the phrase ‘visually stunning’ would seem a tad half-hearted. Gallowwalkers will blow your mind visually. Christ alone knows what this would be like if watched on drugs. You’d never come down.

Snipes has dreadlocks, a dab of grew in his beard, a black hat and flared trousers. Kansa, whom we initially meet bereft of skin like Hellraiser’s Uncle Frank, takes the face and hair of an albino man and then favours a long, purple coat. One of his men wears a sack on his head, another has a heavy metal helmet covered in spikes, a third prefers grafting lizards’ skins onto his head. His dead son is carried everywhere, swaddled in a wickerwork crucifix. As a child, Aman lived in an orphanage until sent out into the world aged 12, whereupon he was adopted by a lady who singlehandedly runs a slaughterhouse. That woman’s daughter was the lover who was raped and murdered. The slaughterhouse and its owner are still there, with a new child apprentice, also an albino. In fact there is a whole community of albinos…

There are a lot of extreme long-shots in this film, emphasising the emptiness of the desert within which this all takes place. There are no ‘western streets’, no saloons and undertakers. Buildings stand in isolation, and sometimes individual figures do too. In an early scene, a long, straight, single-track, narrow-gauge railway leads from nowhere to nowhere. Three static figures dressed in red (looking distractingly like any one of them could shout “No-one expects the Spanish Inquisition!”) approach from far, far away on a hand-trolley powered by a single Chinese coolie. They take a while to arrive, to even become identifiable for what they are. It’s very David Lean.

The closest that Gallowwalkers gets to a town is that small settlement of albinos, though it’s little more than a few randomly arranged huts and a large, newly built gallows where a row of criminals are collectively hanged with a single pull of a lever. There are tall, somewhat wobbly, horse-drawn prison carts. There are cages on the sand. Everything in this film is ‘real’ in the sense of being raw, wooden, hand-built – but equally unreal in seeming a little arch, a tad deliberate, and deliberately so. These sets, these props, these costumes, this make-up – everything has been designed and created for visual effect and the ideas it provokes, artistically designed for both reality and unreality but certainly not for realism. Therein lies much of the film’s power.

To be honest, it’s not even clear if we’re actually mean to be in the Old West; there’s certainly no reference to any real locations in the dialogue. Gallowwalkers was filmed in Namibia (specifically just outside Swakopmund) where there are great expanses of desert that don’t really look like the southern USA. Huge sweeping dunes are an African thing more than an American one and, after El Topo, the next most obvious visual reference is probably Dust Devil. The one cow we ever see in the slaughterhouse – pretty much the only animal on screen apart from horses and a few goats – is very obviously an African zebu, not a North American steer. There is even a brief cutaway shot of a sidewinder at one point, and you certainly don’t get those in Nevada! Such inclusion of anomalous fauna must be deliberate and serves, like the famous armadillo in the 1931 Dracula, to emphasise the otherworldliness of the setting. Dracula couldn’t actually be set in Europe, despite all the evidence, and Gallowwalkers can’t actually be set in North America.

There’s also maybe something of a Japanese influence in the film. Characters spend a lot of time standing still, eventually moving suddenly, like in the best samurai films. Parallels between the western genre and the samurai genre are legion, so perhaps this sort of comparison is almost inevitable in a film this stylised. While we’re at it, Kansa and his cohorts will put you in mind of the Mad Max films. So that’s an Australian influence too. All this in a British film with an American star shot in a former German colony in southern Africa. Gallowwalkers really is set everywhere and nowhere.

In respect of all the above Andrew Goth’s third feature is a truly cinematic experience. Some people, suckered in by the ‘zombie western’ idea, might understandably have been disappointed to find that this isn’t just Dawn of the Dead with spurs. That’s fair enough. But what surprised me the most when leafing through online reviews and comments was how many people complained that they couldn’t follow what was going on. Some people apparently didn’t realise that the scenes of Aman killing Kansa and his gang in jail are flashbacks. Even though Snipes looks completely different (no dreads, no beard, no hair, with tribal markings painted on his face) and the cinematography is notably different too.

This really isn’t a hard film to follow. As evidence of that: I can follow it, and I’m not renowned for grasping the intricacies of multi-level plots. Yes, there are flashbacks. Yes, the story is revealed to us piecemeal instead of in a linear, chronological fashion (or a walloping infodump). That’s cinema folks. If you can’t follow this, good luck with Memento or Pulp Fiction…

More justifiable are complaints from some who have seen this that chunks of the film don’t seem to make sense, serve a purpose or connect to anything else. It’s full of dead ends and unexplained introductions (not necessarily in that order). As criticisms go, this is entirely justified.

For example, there’s a group of prisoners whose guards are shot. Aman takes one young man on as a sidekick. But among the other prisoners are a feisty showgirl/thief and a presumably corrupt priest. These two make other appearances but don’t seem to tie in to the main narrative in any significant way. It’s like they’re meant to be major characters, but aren’t. The opening scenes with the railway, the three guys in red and a guy with a distinctive neck-brace, don’t really make much sense, even after we discover much later that the three ‘cardinals’ are part of Kansa’s gang and Neck-brace was the guard who shot Aman. Did I mention that the lead cardinal has his lips sewn together, but is somehow still able to talk? I suspect some of the ADR on this film may not match with what the characters were originally saying (or attempting to say)…

In fact, if there is one thing that is abundantly clear when watching this film, it’s that the movie has had some serious changes made in post-production. Numerous reviewers have complained that the ‘script’ doesn’t make sense but this is so obviously not what was originally written. Full disclosure: from previous correspondence with Joanne Reay I am aware that the finished film is not what Goth and Reay intended and they’re not exactly happy with what was released. But Jesus, even if I didn’t have that email, I’d be able to work it out. Even allowing for the hallucinatory, trippy nature of the story, settings and characters, there are so many anomalies here – so many things missing and so many things present but in the wrong order – that this simply can’t have been what was intended. Like Strippers vs Werewolves, like The Haunting of Ellie Rose, what you see when you sit down to watch Gallowwalkers is very definitely not the director’s cut.

Yet, while this is evident (to anyone reasonably awake who has seen more than three films in their life), it doesn’t matter as much as some reviewers (and possibly the film-makers) believe. The nature of the film, the stylish, stylistic and symbolic, the mystical, metaphorical and metaphysical, the non-realistic, non-linear but non-arbitrary nature of the artwork that pins our eyes open (and ears: music by Stephen Warbeck and Adrian Glen) is sufficiently ‘out there’ that these lacunae and non-sequiturs blend right in. We don’t really need an explanation for the albino colony any more than we need justification for the anomalous snake and cow. This is a film that wants you to free your mind.

The quality of a really good movie can shine through a lesser cut. Even the shortest edit of The Wicker Man is still a classic. The imposition of narration on Blade Runner didn’t stop it from being instantly recognised by many people as a brilliant film. Even the BBFC-trimmed version of Curse of the Werewolf can be seen for the superior Hammer chiller that it is. The fact that the censors chopped so much out of the ending doesn’t lessen the quality of what precedes that butchery, and the fact that it is externally mandated butchery of the film is screamingly obvious. One would be a fool to blame Terence Fisher or Anthony Hinds for the sudden, arbitrary ending of that cut of Werewolf, just as one would be foolish to blame Anthony Shaffer or Robin Hardy for apparently not establishing Sgt Howie’s character with some sort of prologue. (Or indeed lambasting David Peoples, Hampton Fancher or Ridley Scott – or even Philip K Dick! – for relying too much on the crutch of film noir-style narration and tacking on a happy ending.) Christopher Lee always maintained there was a much better version of The Wicker Man in landfill under a motorway somewhere. Maybe there is, but it must be bloody fantastic because what we have is pretty damn good to start with.

How far does the released version of Gallowwalkers deviate from what Goth and Reay wrote and set out to make? We just don’t know. They have been understandably reluctant to discuss the film. Does a finished version of what we might term ‘The Director’s Cut’ actually exist? Might we ever see it and make a comparison? To be honest, that seems unlikely. People clamoured for a more artistically true, less obviously commercial version of Blade Runner and The Wicker Man, creating a market for revisions and reversions. I’d love to watch Goth’s prefered cut of Gallowwalkers but not many people have seen the film in the first place and I suspect very few of those are hankering to see it again. Which is a shame.

Gallowwalkers wasn’t always called Gallowwalkers. It started life as a script called The Wretched which was set to star Chow Yun-Fat of all people! Which is interesting because the use of a Chinese protagonist in a Wild West setting harks back to – no, not Shanghai Noon! – back to 1970s TV series Kung Fu. You recall: David Carradine played Kwai Chang Caine, a shaolin warrior travelling through the Wild West, back in the days when you could cast a Caucasian actor as an Asian character and nobody batted an eyelid (except all the Asian actors who couldn’t get decent parts). In terms of the ‘mystical western’ subgenre, Kung Fu is definitely the original text and its (indirect) influence on Gallowwalkers is clear.

On the subject of race, it’s interesting that absolutely no reference is made in the film to Aman being black. It’s immaterial. That in itself contributes to the non-realism and other-worldliness of the setting. For a more historically accurate depiction of how race was viewed in that time and place, try watching Blazing Saddles. (Aside from Snipes and the actor playing young Aman in flashbacks, there is one other black actor in the film although he is so heavily made-up that you probably won’t recognise him. Mosca, the guy working for Kansa who prefers to cover his head with lizard skin, is played by the living legend that is Derek Griffiths! He’s come a long way since Play School…)

The promotional website for The Wretched still exists, including a detailed synopsis. Chow Yun-Fat’s character is named Rellik and the sidekick he takes on (called Fabulos in the finished film, played by Riley Smith: Voodoo Academy) is named Twenty-One. (Although not stated in the synopsis, this is because he has six fingers on one hand.) Remember what I said about how difficult I find it to follow complex storylines? Well, the synopsis for The Wretched has me beat. I’ve no idea what’s going on. What is obvious, however, is that not only is it very, very different to the released version of Gallowwalkers, it’s so utterly different that it must also be very different to Andrew Goth’s intended cut of the film. There are a handful of recognisable moments/elements and one consistent character name (Skullbucket, the guy with the big metal helmet) but apart from the basic premise – gunman hunts down resurrected dead bad guys in the Old West – The Wretched and Gallowwalkers are essentially different films.

Under the shooting title Gallowwalker (singular) the film was shot in the Namib Desert in October 2006 with an announced budget of $14 million. Snipes was a big star at the time, just a couple of years on from Blade: Trinity, so it was quite a shock when he was charged with tax evasion. The production had to be put on hold for a while so that he could fly back to the States and arrange his bail. The film wrapped just before Christmas and all the props and costumes were sold off. Somebody in Namibia got Kevin Howarth’s awesome purple coat.

…which was slightly inconvenient because in May 2009 the production restarted for pick-ups and some reshoots in America (either Mexico or the southern USA). Snipes was trying to cram all his various acting commitments into a limited time before heading off to pokey for three years so there was only a couple of weeks to get everything together. Fortunately production manager Carol Muller was able to track down all the required props and costumes and either buy them back or rent them.

I would imagine that these reshoots are where the film diverged from Goth and Reay’s original vision as the press report I’ve seen doesn’t mention Goth at all. So it’s entirely possible he didn’t even direct these bits (whatever they are). Interestingly, this press story is also the only mention I’ve come across of Gallowwalker(s) being conceived as the first part of a trilogy. Although Rudolf Buttendach is the credited editor, Peter Hollywood (Elfie Hopkins) gets an 'Additional Editor' credit which looks suspiciously like an acknowledgement that he was hired to cut together the new version, especially as on his FilmandTVPro page he cites the production company as Boundless Pictures. (Boundless, headed by Brandon Burrows and Courtney Lauren Penn is credited prodco on the film, although the credit block just reads 'Jack Bowyer presents...'.)

Before these reshoots there had been talk of a 2008 release, with Tim Bradstreet allegedly creating a prequel comic-book. A trailer was released in 2008 using comic-book-style graphics to link images. I think all the trailer footage is in the finished film but the lips-sewn-together guy definitely has a different voice. Note that the credited prodcos are not Boundless or Jack Bowyer but Sheer Films (Goth and Reay's own company) and Intandem Films. The absence of Intandem's Gary Smith from the final list of executive producers on the film is quite telling.)

Eventually, six years after it was made, Gallowwalkers finally - and very suddenly - appeared. Its world premiere was on 6th October 2012 at Grimmfest in Manchester (not Frightfest as the Inaccurate Movie Database claims, although it was screened as part of a Frightfest all-nighter in October 2014). I’d like to quote the Grimmfest synopsis here because this guy hits the nail right on the head and should have been plastered all over the DVD sleeve:

The Bastard Love Child Of… BLADE and DUSTDEVIL

Achieving a degree of infamy as the film Wesley Snipes was shooting when he was busted for Tax Evasion, this startling, surreal, supernatural Spaghetti Western combines the visual panache of Sergios Leone and Corbucci with a wild, weird and woolly narrative that plays like something Garth Ennis, Alejandro Jodorowsky and Joe R. Lansdale might dream up between them over several bottles of mescal. Part violent revenge drama, part metaphysical quest, with its tongue partly in its cheek, a morbid quip on its lips and a gun always at the ready, this is destined to become a massive cult favourite. And you saw it here first.

The first home release was the US DVD from Lions Gate in August 2013, followed by discs in Germany (August 2013), the UK (May 2014), then France, Japan, Italy, Mexico, Brazil and maybe some other territories too. What looked like it might become a ‘lost film’ is now widely available.

But people look at this movie and think well gee, if it took six or seven years to get released straight to DVD then it must be terrible. Especially if the star got arrested halfway through production. So viewers are prejudiced before they even put the disc in the machine. They don’t know what to expect, they don’t know the background or the context. Hopefully this review will go a little way towards re-evaluating Gallowwalkers in the perception of horror fans.

But people look at this movie and think well gee, if it took six or seven years to get released straight to DVD then it must be terrible. Especially if the star got arrested halfway through production. So viewers are prejudiced before they even put the disc in the machine. They don’t know what to expect, they don’t know the background or the context. Hopefully this review will go a little way towards re-evaluating Gallowwalkers in the perception of horror fans.

Alongside those actors already mentioned, the cast includes Tanit Phoenix (no relation to River) as Aman’s lover, Patrick Bergin as a lawman, Steven Elder (also in Cold and Dark) as the priest, Simona Behlikova (also in werewolf-free British werewolf picture Lycanthropy) as Kansa’s woman, wrestler ‘Diamond' Dallas Page as Skullbucket and hell yeah, Derek Griffiths. DG is The Man as far as I’m concerned. Give him an honorary Bafta right now.

Goth and Reay followed this with the science fiction movie DxM (previously Deus Ex Machina) which likewise premiered at Grimmfest. After finishing his sentence for tax evasion, Snipes set about picking up his acting career including a gig on The Expendables 3.

I’ll wrap up with the only words I can find from Andrew Goth about his film, which were quoted on a poster that said the film was in post (so presumably 2007):

“With Gallowwalker [sic] we are creating a new hero in a mythic western world. Like the best of the spaghetti westerns, Aman’s story is one of blood and vengeance, but his nemesis is unlike any that we have seen before. Kansa was a bad man when he was alive and now he’s back from the dead and relishing his supernatural prowess. Their story plays out against vast desert landscapes that underscore the epic state of their battle. We shot on 2-perf, as Sergio Leone did, which gives super-wide scope. This retro feel is being enhanced by the latest digital capabilities, which allows us to colour the film in a surreal way and creates a graphic novel feel.” – Andrew Goth, director

MJS rating: A-

Writers: Andrew Goth, Joanne Reay

Producers: Brandon Burrows, Courtney Lauren Penn

Cast: Wesley Snipes, Kevin Howarth, Riley Smith

Country: UK/USA

Year of release: 2013 (eventually…)

Reviewed from: UK DVD

Gallowwalkers does not come with a good reputation. Eleven per cent on Rotten Tomatoes. Average 3.6/10 on IMDB. Average 2.5 stars on Amazon. Most people who have expressed an opinion on it seemed to have been pretty negative. Received opinion is that the film is a clunker.

Well, I’m here to fly in the face of received opinion. I’ve watched Gallowwalkers and while even I hesitate to say it’s great, nevertheless it has undeniable elements of greatness. It also has undeniable flaws – what those are and why they exist I’ll come to in due course – but they are more than compensated for by the film’s positive aspects. I enjoyed it enormously.

Bear in mind that I also appreciated Andrew Goth and Joanne Reay’s previous film, Cold and Dark, which I described in Urban Terrors as “a curious but not unenjoyable melding of police procedural with weird horror.” That film has also been poorly regarded by most critics and punters. Maybe I’m just in tune with what these guys are trying to do.

Gallowwalkers has been described as a ‘zombie western’ but that’s misleading. Films like Cowboys and Zombies and Devil’s Crossing simply place a standard zombie scenario into a Wild West setting. Gallowwalkers is set in something approaching the 19th century American frontier and features characters who return to life, but there any similarities end. This isn’t just a horror film, certainly not just a western. It’s a mystical film, playing on the tropes of the more extreme end of the western genre, beyond Sergio Leone, beyond the old Django movies. Where some westerns are defined simply by iconography – Stetsons, six-shooters, steers and saloons – the real heart of the western genre lies in the themes it explores. Divorced from both the urban and the rural, divorced from both history and modernity, the best westerns are about isolation, struggle, identity, a quest for something undefined, perhaps even unreachable. Great westerns use the frontier of civilisation as a metaphor for the frontiers inside the protagonist’s mind and soul. All great westerns have a mystical element to them, however low it may be in the mix.

Occasionally a western comes along which ramps up the mystical element to eleven. The most famous example of that – and the most obvious comparison for Gallowwalkers, just in terms of its startling imagery and adamant non-realism – would be El Topo. Like Jodorowsky, Andrew Goth uses the western genre and some of its tropes to explore bigger, weirder, stranger ideas – just as he used the police procedural genre in Cold and Dark.

Does it always work? We’ll come to that.

So here’s the surprisingly straightforward plot, as eventually revealed through assorted flashbacks and revelations. Yer man Wesley Snipes is Aman (“a man” = everyman?), who swore revenge on the bastards who raped and murdered the girl he loved. He tracked them down to a jail and shot them in their cells but, in escaping, was himself shot by one of the jailers. His adopted mother called on the Devil to save her son and was granted her wish. But in returning Aman to life, the Devil decreed that those he killed would also return to life.

So those particular bastards are once again walking and talking, led by the thoroughly amoral Kansa (my old mate Kevin Howarth: The Last Horror Movie, The Seasoning House). Or at least, most of them are. Kansa doesn’t know how or why he and his men were reanimated, and hence he doesn’t know why his son wasn’t. Aman is on a quest to kill Kansa and his men, aiming to make sure they stay dead by ripping their fucking heads off. Kansa meanwhile is on a quest to find some mystical nuns whom he believes will be able to restore his son to life.

That’s it in a nutshell but there are all sorts of excursions to the plot, not all of which go anywhere in particular. What matters, more than the plot, are the individual scenes and the truly extraordinary imagery within those scenes. A combination of Goth’s direction, Goth and Reay’s screenplay, Henner Hofmann’s cinematography, Laurence Borman’s production design, Pierre Viening’s costumes and a make-up department overseen by the hugely experienced Jackie Fowler (with designs by the legendary Paul Hyett) – all of this creates a film for which the phrase ‘visually stunning’ would seem a tad half-hearted. Gallowwalkers will blow your mind visually. Christ alone knows what this would be like if watched on drugs. You’d never come down.

There are a lot of extreme long-shots in this film, emphasising the emptiness of the desert within which this all takes place. There are no ‘western streets’, no saloons and undertakers. Buildings stand in isolation, and sometimes individual figures do too. In an early scene, a long, straight, single-track, narrow-gauge railway leads from nowhere to nowhere. Three static figures dressed in red (looking distractingly like any one of them could shout “No-one expects the Spanish Inquisition!”) approach from far, far away on a hand-trolley powered by a single Chinese coolie. They take a while to arrive, to even become identifiable for what they are. It’s very David Lean.

The closest that Gallowwalkers gets to a town is that small settlement of albinos, though it’s little more than a few randomly arranged huts and a large, newly built gallows where a row of criminals are collectively hanged with a single pull of a lever. There are tall, somewhat wobbly, horse-drawn prison carts. There are cages on the sand. Everything in this film is ‘real’ in the sense of being raw, wooden, hand-built – but equally unreal in seeming a little arch, a tad deliberate, and deliberately so. These sets, these props, these costumes, this make-up – everything has been designed and created for visual effect and the ideas it provokes, artistically designed for both reality and unreality but certainly not for realism. Therein lies much of the film’s power.

To be honest, it’s not even clear if we’re actually mean to be in the Old West; there’s certainly no reference to any real locations in the dialogue. Gallowwalkers was filmed in Namibia (specifically just outside Swakopmund) where there are great expanses of desert that don’t really look like the southern USA. Huge sweeping dunes are an African thing more than an American one and, after El Topo, the next most obvious visual reference is probably Dust Devil. The one cow we ever see in the slaughterhouse – pretty much the only animal on screen apart from horses and a few goats – is very obviously an African zebu, not a North American steer. There is even a brief cutaway shot of a sidewinder at one point, and you certainly don’t get those in Nevada! Such inclusion of anomalous fauna must be deliberate and serves, like the famous armadillo in the 1931 Dracula, to emphasise the otherworldliness of the setting. Dracula couldn’t actually be set in Europe, despite all the evidence, and Gallowwalkers can’t actually be set in North America.

In respect of all the above Andrew Goth’s third feature is a truly cinematic experience. Some people, suckered in by the ‘zombie western’ idea, might understandably have been disappointed to find that this isn’t just Dawn of the Dead with spurs. That’s fair enough. But what surprised me the most when leafing through online reviews and comments was how many people complained that they couldn’t follow what was going on. Some people apparently didn’t realise that the scenes of Aman killing Kansa and his gang in jail are flashbacks. Even though Snipes looks completely different (no dreads, no beard, no hair, with tribal markings painted on his face) and the cinematography is notably different too.

This really isn’t a hard film to follow. As evidence of that: I can follow it, and I’m not renowned for grasping the intricacies of multi-level plots. Yes, there are flashbacks. Yes, the story is revealed to us piecemeal instead of in a linear, chronological fashion (or a walloping infodump). That’s cinema folks. If you can’t follow this, good luck with Memento or Pulp Fiction…

More justifiable are complaints from some who have seen this that chunks of the film don’t seem to make sense, serve a purpose or connect to anything else. It’s full of dead ends and unexplained introductions (not necessarily in that order). As criticisms go, this is entirely justified.

For example, there’s a group of prisoners whose guards are shot. Aman takes one young man on as a sidekick. But among the other prisoners are a feisty showgirl/thief and a presumably corrupt priest. These two make other appearances but don’t seem to tie in to the main narrative in any significant way. It’s like they’re meant to be major characters, but aren’t. The opening scenes with the railway, the three guys in red and a guy with a distinctive neck-brace, don’t really make much sense, even after we discover much later that the three ‘cardinals’ are part of Kansa’s gang and Neck-brace was the guard who shot Aman. Did I mention that the lead cardinal has his lips sewn together, but is somehow still able to talk? I suspect some of the ADR on this film may not match with what the characters were originally saying (or attempting to say)…

In fact, if there is one thing that is abundantly clear when watching this film, it’s that the movie has had some serious changes made in post-production. Numerous reviewers have complained that the ‘script’ doesn’t make sense but this is so obviously not what was originally written. Full disclosure: from previous correspondence with Joanne Reay I am aware that the finished film is not what Goth and Reay intended and they’re not exactly happy with what was released. But Jesus, even if I didn’t have that email, I’d be able to work it out. Even allowing for the hallucinatory, trippy nature of the story, settings and characters, there are so many anomalies here – so many things missing and so many things present but in the wrong order – that this simply can’t have been what was intended. Like Strippers vs Werewolves, like The Haunting of Ellie Rose, what you see when you sit down to watch Gallowwalkers is very definitely not the director’s cut.

Yet, while this is evident (to anyone reasonably awake who has seen more than three films in their life), it doesn’t matter as much as some reviewers (and possibly the film-makers) believe. The nature of the film, the stylish, stylistic and symbolic, the mystical, metaphorical and metaphysical, the non-realistic, non-linear but non-arbitrary nature of the artwork that pins our eyes open (and ears: music by Stephen Warbeck and Adrian Glen) is sufficiently ‘out there’ that these lacunae and non-sequiturs blend right in. We don’t really need an explanation for the albino colony any more than we need justification for the anomalous snake and cow. This is a film that wants you to free your mind.

The quality of a really good movie can shine through a lesser cut. Even the shortest edit of The Wicker Man is still a classic. The imposition of narration on Blade Runner didn’t stop it from being instantly recognised by many people as a brilliant film. Even the BBFC-trimmed version of Curse of the Werewolf can be seen for the superior Hammer chiller that it is. The fact that the censors chopped so much out of the ending doesn’t lessen the quality of what precedes that butchery, and the fact that it is externally mandated butchery of the film is screamingly obvious. One would be a fool to blame Terence Fisher or Anthony Hinds for the sudden, arbitrary ending of that cut of Werewolf, just as one would be foolish to blame Anthony Shaffer or Robin Hardy for apparently not establishing Sgt Howie’s character with some sort of prologue. (Or indeed lambasting David Peoples, Hampton Fancher or Ridley Scott – or even Philip K Dick! – for relying too much on the crutch of film noir-style narration and tacking on a happy ending.) Christopher Lee always maintained there was a much better version of The Wicker Man in landfill under a motorway somewhere. Maybe there is, but it must be bloody fantastic because what we have is pretty damn good to start with.

Gallowwalkers wasn’t always called Gallowwalkers. It started life as a script called The Wretched which was set to star Chow Yun-Fat of all people! Which is interesting because the use of a Chinese protagonist in a Wild West setting harks back to – no, not Shanghai Noon! – back to 1970s TV series Kung Fu. You recall: David Carradine played Kwai Chang Caine, a shaolin warrior travelling through the Wild West, back in the days when you could cast a Caucasian actor as an Asian character and nobody batted an eyelid (except all the Asian actors who couldn’t get decent parts). In terms of the ‘mystical western’ subgenre, Kung Fu is definitely the original text and its (indirect) influence on Gallowwalkers is clear.

On the subject of race, it’s interesting that absolutely no reference is made in the film to Aman being black. It’s immaterial. That in itself contributes to the non-realism and other-worldliness of the setting. For a more historically accurate depiction of how race was viewed in that time and place, try watching Blazing Saddles. (Aside from Snipes and the actor playing young Aman in flashbacks, there is one other black actor in the film although he is so heavily made-up that you probably won’t recognise him. Mosca, the guy working for Kansa who prefers to cover his head with lizard skin, is played by the living legend that is Derek Griffiths! He’s come a long way since Play School…)

The promotional website for The Wretched still exists, including a detailed synopsis. Chow Yun-Fat’s character is named Rellik and the sidekick he takes on (called Fabulos in the finished film, played by Riley Smith: Voodoo Academy) is named Twenty-One. (Although not stated in the synopsis, this is because he has six fingers on one hand.) Remember what I said about how difficult I find it to follow complex storylines? Well, the synopsis for The Wretched has me beat. I’ve no idea what’s going on. What is obvious, however, is that not only is it very, very different to the released version of Gallowwalkers, it’s so utterly different that it must also be very different to Andrew Goth’s intended cut of the film. There are a handful of recognisable moments/elements and one consistent character name (Skullbucket, the guy with the big metal helmet) but apart from the basic premise – gunman hunts down resurrected dead bad guys in the Old West – The Wretched and Gallowwalkers are essentially different films.

Under the shooting title Gallowwalker (singular) the film was shot in the Namib Desert in October 2006 with an announced budget of $14 million. Snipes was a big star at the time, just a couple of years on from Blade: Trinity, so it was quite a shock when he was charged with tax evasion. The production had to be put on hold for a while so that he could fly back to the States and arrange his bail. The film wrapped just before Christmas and all the props and costumes were sold off. Somebody in Namibia got Kevin Howarth’s awesome purple coat.

…which was slightly inconvenient because in May 2009 the production restarted for pick-ups and some reshoots in America (either Mexico or the southern USA). Snipes was trying to cram all his various acting commitments into a limited time before heading off to pokey for three years so there was only a couple of weeks to get everything together. Fortunately production manager Carol Muller was able to track down all the required props and costumes and either buy them back or rent them.

I would imagine that these reshoots are where the film diverged from Goth and Reay’s original vision as the press report I’ve seen doesn’t mention Goth at all. So it’s entirely possible he didn’t even direct these bits (whatever they are). Interestingly, this press story is also the only mention I’ve come across of Gallowwalker(s) being conceived as the first part of a trilogy. Although Rudolf Buttendach is the credited editor, Peter Hollywood (Elfie Hopkins) gets an 'Additional Editor' credit which looks suspiciously like an acknowledgement that he was hired to cut together the new version, especially as on his FilmandTVPro page he cites the production company as Boundless Pictures. (Boundless, headed by Brandon Burrows and Courtney Lauren Penn is credited prodco on the film, although the credit block just reads 'Jack Bowyer presents...'.)

Before these reshoots there had been talk of a 2008 release, with Tim Bradstreet allegedly creating a prequel comic-book. A trailer was released in 2008 using comic-book-style graphics to link images. I think all the trailer footage is in the finished film but the lips-sewn-together guy definitely has a different voice. Note that the credited prodcos are not Boundless or Jack Bowyer but Sheer Films (Goth and Reay's own company) and Intandem Films. The absence of Intandem's Gary Smith from the final list of executive producers on the film is quite telling.)

Eventually, six years after it was made, Gallowwalkers finally - and very suddenly - appeared. Its world premiere was on 6th October 2012 at Grimmfest in Manchester (not Frightfest as the Inaccurate Movie Database claims, although it was screened as part of a Frightfest all-nighter in October 2014). I’d like to quote the Grimmfest synopsis here because this guy hits the nail right on the head and should have been plastered all over the DVD sleeve:

The Bastard Love Child Of… BLADE and DUSTDEVIL

Achieving a degree of infamy as the film Wesley Snipes was shooting when he was busted for Tax Evasion, this startling, surreal, supernatural Spaghetti Western combines the visual panache of Sergios Leone and Corbucci with a wild, weird and woolly narrative that plays like something Garth Ennis, Alejandro Jodorowsky and Joe R. Lansdale might dream up between them over several bottles of mescal. Part violent revenge drama, part metaphysical quest, with its tongue partly in its cheek, a morbid quip on its lips and a gun always at the ready, this is destined to become a massive cult favourite. And you saw it here first.

The first home release was the US DVD from Lions Gate in August 2013, followed by discs in Germany (August 2013), the UK (May 2014), then France, Japan, Italy, Mexico, Brazil and maybe some other territories too. What looked like it might become a ‘lost film’ is now widely available.

But people look at this movie and think well gee, if it took six or seven years to get released straight to DVD then it must be terrible. Especially if the star got arrested halfway through production. So viewers are prejudiced before they even put the disc in the machine. They don’t know what to expect, they don’t know the background or the context. Hopefully this review will go a little way towards re-evaluating Gallowwalkers in the perception of horror fans.

But people look at this movie and think well gee, if it took six or seven years to get released straight to DVD then it must be terrible. Especially if the star got arrested halfway through production. So viewers are prejudiced before they even put the disc in the machine. They don’t know what to expect, they don’t know the background or the context. Hopefully this review will go a little way towards re-evaluating Gallowwalkers in the perception of horror fans.Alongside those actors already mentioned, the cast includes Tanit Phoenix (no relation to River) as Aman’s lover, Patrick Bergin as a lawman, Steven Elder (also in Cold and Dark) as the priest, Simona Behlikova (also in werewolf-free British werewolf picture Lycanthropy) as Kansa’s woman, wrestler ‘Diamond' Dallas Page as Skullbucket and hell yeah, Derek Griffiths. DG is The Man as far as I’m concerned. Give him an honorary Bafta right now.

Goth and Reay followed this with the science fiction movie DxM (previously Deus Ex Machina) which likewise premiered at Grimmfest. After finishing his sentence for tax evasion, Snipes set about picking up his acting career including a gig on The Expendables 3.

I’ll wrap up with the only words I can find from Andrew Goth about his film, which were quoted on a poster that said the film was in post (so presumably 2007):

“With Gallowwalker [sic] we are creating a new hero in a mythic western world. Like the best of the spaghetti westerns, Aman’s story is one of blood and vengeance, but his nemesis is unlike any that we have seen before. Kansa was a bad man when he was alive and now he’s back from the dead and relishing his supernatural prowess. Their story plays out against vast desert landscapes that underscore the epic state of their battle. We shot on 2-perf, as Sergio Leone did, which gives super-wide scope. This retro feel is being enhanced by the latest digital capabilities, which allows us to colour the film in a surreal way and creates a graphic novel feel.” – Andrew Goth, director

MJS rating: A-

Thursday, 14 July 2016

Snaker

Director: Mr Fai Samang

Writers: Mr Fai Sam Ang, Mrs Mao Samnang

Producer: Mr Thunya Nilklang

Cast: Mr Vinal Kraybotr (Winai Kraibutr), Miss Pich Chan Barmey, Mr Tep Rindaro, Mrs Om Portevy

Year of release: 2001

Country: Cambodia/Thailand

Reviewed from: Hong Kong VCD (Winson Entertainment)

Now this is a film I’ve been wanting to see for a while, the first Cambodian feature film for years (even if it is a co-production with a Thai company) and a premier example of the prolific snake-woman genre.

Nhi (Om Portevy aka Ampor Tevy, star of a popular TV soap) lives in the forest with her boorish, alcoholic husband Manop and their about-twelve-year-old daughter Ed. One day Nhi and Ed encounter a giant, talking snake in the forest while looking for bamboo shoots - they have lost their spade and the snake agrees to let them have it back if Nhi will love him and be his wife. Mohap is away in the city (where he sells jewellery) so that night the giant snake crawls into Nhi’s bed and transforms into a handsome man who makes love to her. Afterwards, Nhi is frequently seen by her daughter stroking the snake and talking lovingly to it.

I tell you, folks, this thing is a Freudian’s dream!

In the city we meet rich art dealer Wiphak and his wife Buppha, who is pregnant. When their friends Pokia and Mora discover this, Mora decides to become pregnant too and goes to a local witch for a potion which will make Pokia subservient to her, and therefore compliable.

Back in the forest, Mopak returns and notices Nhi’s bump, the result of her tryst with the Snake King (he’s not actually named as such, but one of the alternative English language titles of this film is The Snake King’s Daughter). Mopak accuses his wife of being unfaithful because they haven’t had sex for months, but she points out that no-one else lives within miles of them and claims that he was drunk at the time.

Ed tells her father about the snake but begs him not to hurt her mother. He follows his daughter to where the snake lives and cuts its head off. This is very clearly a genuine shot of a live snake being cut in two with a machete, and though it’s brief it’s a bit disturbing. He also makes Nhi eat the cooked snake meat. Then he takes her to the river, ostensibly to bathe, where he kills her for being unfaithful by slicing open her swollen belly. Out pours plenty of blood and a dozen or so small snakes which Manop kills (again for real). One tiny snake escapes and as Manop goes after it he slips on a rock and falls on his own sword. Ed finds her dead parents and also slips on a rock, cracks her head open and dies.

But a passing holy man finds the surviving snakelet and sees it transform into a baby as the sun rises. He takes the child home, naming it Soraya after the sun.

Scoot forward ten years or so and Soraya is a girl, rebellious but not disrespectful, living in a cave with her ‘grandfather’. But she is not any girl, for her head is a mass of writhing snakes!

This is one of the most interesting aspects of this film. Famously, when Hammer Films made The Gorgon in 1964, actress Barbara Shelley offered to play the title role wearing a headpiece with some live grass snakes attached (provided that the RSPCA were happy with the set-up). Unfortunately, the producers decided instead to depict the transmogrified version of Shelley’s character using a different actress (Prudence Hyman) with a headpiece that looked fine in stills but was obviously a bunch of rubber snakes when seen on screen.

Snakes are supposed to move. They writhe, they wriggle. And these ones do!

Because the makers of Snaker have used that very same technique: most of the snakes are actually still rubber but there are enough live ones attached to provide sufficient movement that it genuinely does look like a writhing mass of snakes on the actress’ head. It was astounding enough when Nhi lay down with the giant snake - a huge python (I think) which must have been twelve feet long if it was an inch. And it was disturbing enough when we had that real snake-beheading shot. But here we have live snakes not just stuck on somebody’s head but stuck on the head of a thirteen-year-old girl!

The actress who plays young Soraya, it must be said, is very good anyway (so was the girl playing Ed, to be fair) but for her to be able to act while live snakes hang in front of her face is surely worthy of some sort of award. (According to a piece about this film in the New York Times, young Soraya is played by Ms Danh Monica, although there is no name like that in the credits.)

Anyway, down at the river Soraya - with her head covered - meets three children of about her age (ten or eleven). These are Veha, son of the kindly Wiphak and Buppha (who died in childbirth), and Kiri and Reena, son and daughter of the snobbish Pokia and Mora. Veha and Reena are devoted to each other, according to their parents at least. Soraya asks to join their game of hide and seek, and though Veha is welcoming, Reena is rude and asks her brother to get rid of the new girl. He pulls the wrap from Soraya’s head - and the three children understandably run away screaming, while Soraya returns, tearfully to her grandfather.

A caption tells us it’s ten years later, so of course by now all four kids are young men and women. Returning to the river, kind-hearted Veha (Vinal Kraybotr: Nang Nak, Krai Thong, Kaew Kon Lek) gets into a fight with aggressive Kiri, who pushes him over a waterfall. Kiri and his sister head back to town and tell a distraught Wiphak that his son fell accidentally and, though they searched, there was no sign of him.

But of course, Veha isn’t dead - he is found and nursed back to health by Soraya, now played by Pich Chan Barmey (aka Pich Chanboramey). He’s handsome, she’s beautiful; his name means sky, hers means sun; they both have good hearts - so of course they start to fall for each other, especially as Grandfather has given Soraya a magic ring which transforms her snakes into beautiful long hair.

Veha and Soraya return to his overjoyed father, where Reena is understandably jealous of the new arrival because she and Veha have technically been engaged since they were children. Mora and Reena go to see the old witch who gives them some more of the bewitching potion that worked twenty years earlier on Pokia; they put it in Veha’s goblet at dinner but Soraya’s magic ring warns her and she knocks it from the table.

The witch works out that Soraya is a snake - not a reincarnation of a snake but the real thing - but that her magic powers will be lost if she loses her virginity. So Kiri sneaks into Wiphak’s house and tries to rape Soraya, but her hair turns back into snakes, one of which falls off and bites Kiri, killing him instantly.

There then follows one of the most unsubtle tourism product placements you are ever likely to see, although as Snaker was the first Cambodian feature film to receive international distribution for many years, it is perhaps allowable. Veha and Soraya spend several minutes wandering around the magnificent ruins of Ankor Wat, and Veha tells her that his love for her is as strong and everlasting as the temple walls.

Eventually, the two young lovers do sleep together, and while Veha sleeps, Soraya finds patches of snake skin on her arms. She runs back to her grandfather, but Mora and Reena appear with the old witch, who battles the holy man in a pretty cool magic fight, which leaves both of them dead. Mora and Reena run away but are bitten by a snake, as Kiri was. The Snake King reappears, along with the magically revived grandfather, and they use their combined power to make Soraya fully, permanently human - just as Veha appears to sweep her off her feet and carry her home.

What a great film! It’s got romance, action, intrigue, fantasy, and even a travelogue in the middle. It does have at least one snake deliberately and unpleasantly killed in the name of entertainment, which may be okay in Cambodia but is not a terribly bright idea for a potential export. But given how out of step with global popular culture the Cambodians were during - and in the wake of - the Khmer Rouge regime, again this is sort of allowable.

Pol Pot and his secret police outlawed all forms of popular entertainment including cinemas, so making a Cambodian film was a bit of a gamble as far as domestic distribution goes. It was apparently shown drive-in style at various outside venues. It must be said that, for a country with effectively no cinema industry, this is a fine-looking film. The cinematography is excellent (Mr Saray Chat is credited as cameraman) and the production values are well above the B-movie level that one might expect given the film’s origins. There is no actual special effects credit, but Mr Chhun Achom was responsible for the make-up, which may or may not include getting actresses to wear snakes on their heads!