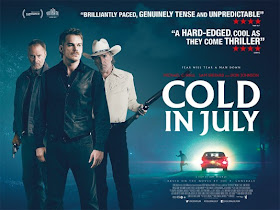

Writers: Jim Mickle, Nick Damici

Producers: Rene Bastian, Linda Moran, Marie Savare

Cast: Michael C Hall, Don Johnson, Sam Shepard

Country: USA

Year of release: 2014

Reviewed from: screener

Joe R Lansdale is one of my absolute favourite authors, and has been for many years. He started out writing horror novels and short stories – he wrote zombie westerns long before it became a thing – and weird science fiction. Over time, his work gradually leaned more towards crime thrillers, but still with horror elements and a darkness that marked the stories as more than just detective fiction.

Like many successful authors, Lansdale’s books have been optioned many times over the years (providing, I imagine, a tidy income) without any progressing beyond development. It was only in 2002 that Don Coscarelli of Phantasm fame brought Lansdale’s work to the big screen with the awesome Bubba Ho-Tep. Which was somewhat ironic because a tale of a geriatric Elvis impersonator defeating a mummy was far more technically complex – and far less obviously commercial – than much of Lansdale’s more mainstream work. His short story ‘Incident On and Off a Mountain Road’ was adapted, again by Coscarelli, as an episode of Masters of Horror. Now comes Cold in July.

Published in 1989, this was a direct and immediate pre-cursor to Lansdale’s most iconic series of novels, the Hap and Leonard books. It’s about ordinary folk getting mixed up in something big and unpleasant and having to step up to the bat to fix it because it’s wrong and somebody’s got to do something about it. There’s a real sense of morality to this story, as there is in the Hap and Leonard books: a sense of right and wrong which transcends the violence, the bad actions, the criminal activity, the lies and deceit. A Lansdale crime thriller is the literary equivalent of somebody stepping in to stop a fight between strangers. It has to be done because walking on by would be the wrong thing to do and there’s no-one else round here gonna do it if you don’t.

The catalyst for Cold in July is the semi-accidental shooting of a burglar. Michael C Hall from Six Feet Under and Dexter stars as Richard Dane, whose occupation we first see typed onto a police report as ‘FRAMER’, leading us to assume he’s a farmer until we find out he actually runs a picture-framing business. He has an elementary school teacher wife (Vinessa Shaw: Stag Night) and a little boy (Brogan Hall) so when he hears an intruder one night, he takes out an old revolver to defend himself. Confronted with a torch, his finger slips, and house-breaker brains are splattered all across his living room.

Nick Damici, who co-wrote the screenplay with director Jim Mickle, plays Ray Price, a cop who assures Dane that everything will be all right. Dane is an upstanding citizen with a clean record, the perp was Freddy Russell, a well-known low-life with a string of convictions, and the whole thing counts as self-defence. The fly in the ointment is Freddy’s ex-con father Ben Russell (Sam Shepard) who wants revenge for the death of his son. Dane’s family are threatened, Price puts them under protection, Russell gets arrested eventually.

But things take an odd turn when Dane sees an old picture of Freddy Russell and realises that this is not the man he killed. Price assures Dane he’s mistaken. In a nice line that makes his profession relevant to the plot, Dane points out that he’s good at recognising faces because he spends all day looking at photographs of people. A further odd incident, which I won’t specify for spoiler reasons, sees Dane team up with the taciturn, brutal Russell, to find out who actually was killed in that living room, what has happened to Freddy Russell, and why the cops are deliberately conflating the two.

But things take an odd turn when Dane sees an old picture of Freddy Russell and realises that this is not the man he killed. Price assures Dane he’s mistaken. In a nice line that makes his profession relevant to the plot, Dane points out that he’s good at recognising faces because he spends all day looking at photographs of people. A further odd incident, which I won’t specify for spoiler reasons, sees Dane team up with the taciturn, brutal Russell, to find out who actually was killed in that living room, what has happened to Freddy Russell, and why the cops are deliberately conflating the two.If there’s a problem with the generally excellent film, it’s that it takes rather too long to get to the point, misleading us into thinking that this will be a film about Dane trying to protect his family from the threat of Russell’s revenge. That would be a perfectly serviceable thriller if that was the plot, but it wouldn’t be a Joe R Lansdale thriller and it’s not the meat of the story. This delay and distraction also means we’re about halfway through the film before we meet the third of our protagonists, retired private detective Jim Bob Luke, played by Don Johnson with very obvious relish.

The biggest joy of reading Lansdale, even more than his clever plots and rich, rewarding characters, is his way with words. His dialogue (and first person narrative) is a laconic East Texas drawl, laced with wry, jet-black, cynicism. In Cold in July, Jim Bob Luke fulfils this role.

Lansdale is Texan. Very Texan. And he writes about Texas (mainly East Texas, in and around Nacogdoches). Now I’ve never been to Texas but I’ve also never been to 1930s England. And I get the impression that Lansdale’s Texas is just slightly exaggerated, or at least highlighted, in the same way that PG Wodehouse’s world was. Jim Bob Luke epitomises his own time and place the same way that Bertie Wooster did – which is probably not a comparison made very often.

Jim Bob Luke drives a bright red convertible with a personalised number plate and bull horns on the front. He wears sequined cowboy shirts and a big white Stetson without a hint of irony. “That’s for my car!” he tells a seven-foot thug after a minor collision, accompanied by a good kick, having first incapacitated the giant with a deft boot to the groin. Then, after the briefest of pauses to consider priorities and collateral damage from the preceding altercation, with another solid kick: “And that’s for my hat!”

If you’re ever asked to sum up the literary oeuvre of Joe R Lansdale in less than five seconds, that’s your clip right there.

With Luke’s help, Dane and Russell uncover what’s going on, peeling back the layers to find that this is not simple police corruption. In fact, it could be argued that the cops are doing the right thing, albeit not in the right way, and with the caveat that what they are doing is, unbeknown to them, allowing something much worse to happen. And to say more would be to ruin the twists and turns of a plot that constantly makes us re-evaluate characters and their actions. Suffice to note that the finale is significantly more violent than anything that has gone before.

There are themes to Cold in July, not least the theme of Fatherhood. Russell loses his son, threatens to take Dane’s, then finds out he hasn’t lost his son after all. This is a film about manhood, about fatherhood, about responsibility. It’s a film which is as thought-provoking as it is gripping, as tense as it is enjoyable. Perhaps this will introduce more people to the work of Joe R Lansdale. Perhaps this will usher in those long-awaited Hap and Leonard adaptations.

Mickle, like Lansdale, comes to dark crime thriller via remarkable horror tales, having previously helmed Mulberry Street, Stake Land and the remake of We Are What We Are. According to the old IMDB, his next project will be a TV series called… Hap and Leonard! Awesome!

Mickle, like Lansdale, comes to dark crime thriller via remarkable horror tales, having previously helmed Mulberry Street, Stake Land and the remake of We Are What We Are. According to the old IMDB, his next project will be a TV series called… Hap and Leonard! Awesome!One final note. Mickle has very sensibly kept the story in 1989. Updating this to a world of cellphones and internet (Jim Bob has a clunky car phone which he shows off with pride) would never work. The story would need to be changed so much in order to maintain the plot points about who knows what and how people find things, that it wouldn’t be the book any more. Kudos to production designer Russell Barnes (Oculus), art director Annie Simeone, set decorator Daniel R Kersting and costume designer Elisabeth Vastola (The Innkeepers, V/H/S) for making the film look believable.

MJS rating: A-

No comments:

Post a Comment