When you directed your first feature, Pep Squad, what were your hopes and ambitions with regards to film-making?

"Well, I had no idea what the reality of that world was, is. I was barely an adult, and so totally naïve. I thought we'd make the movie, it would get picked up by a major distributor (which it nearly did several times), and we’d have instant fame and fortune. And, indeed, we received a lot of notoriety globally – but no fortune. Lloyd Kaufman arranged for the film to premiere at the Cannes Film Festival in France, and Harvey Weinstein called us personally to see the film, as did other mini-majors at the time. Then Columbine happened and none of them would touch it.

"Soon after many of the people who wanted our movie ended up stealing our ideas to make nearly identical movies, such as Jawbreaker. A friend of mine who was a Senior VP of one of the majors told me everyone knew what happened with Pep Squad, so my advice was to just keep making movies, that none of them would expect me to. Funny, many moons later I met Darren Stein and told him what had happened, and he felt really badly. He confessed to getting notes from Jodie Scalla and Clint Culpepper (the people he answered to with Jawbreaker, who were the ones who previously wanted Pep Squad), but pleaded with me to believe him that he didn't outright copy my film on purpose and wouldn't have had he known. He claimed to never have seen Pep Squad, so I sent him a DVD and he hasn't called me since. I can’t imagine his embarrassment. Anyway, to make a long story less long, hahaha, I had absolutely no idea about the real world of filmmaking at the time. Even though I was very confident in my abilities as a filmmaker."

I believe you made a bunch of low-budget films prior to Pep Squad, including an unofficial Anne Rice adaptation. What can you tell me about those?

"Oh, they were horrible. Just terrible. (Laughs out loud). Many of them were made when I attended CalArts film school, and some even when I was even younger. The adaptation of The Vampire Lestat was awkward, but a blast even if totally amateurish. The assignment at CalArts was to make a short film with 'texture' or some kind of weird aesthetic bent. I never made a short film in my life at that point, and only thought of things in long-format storytelling. And I'd just finished reading The Vampire Lestat and thought it would make a marvelous movie. I still do, and think I ought to be the one to make it professionally.

"So I made the thing on VHS or some similarly archaic kind of tape recording device, and sent it to Anne Rice for Valentine’s Day. I don’t remember what she said about it other than 'Thank you,' I'm sure she couldn't bear to watch it. No one could. (Laughs again). I'd filmed the movie in Kansas during a winter break, but stayed gone long enough to finish editing it. When I returned to CalArts ;my teachers asked sternly WHERE HAD I BEEN. I told them I was busy doing “the assignment' and handed them a double-tape VHS box set (the movie was over two hours in length, and at that time a single VHS tape held only two hours of running time). My teachers looked puzzled, and a bit overwhelmed, not sure what to do with me."

There was a big gap between Pep Squad and Firecracker. What changed for you in that time, and what drove those changes?

"Yes, it took many years to find the funding needed to make Firecracker. Most of this process is documented in Wamego Part 1 (Making Movies Anywhere). I think the largest growth during that period was in myself personally. As anyone knows who has experienced it – a person 'grows up' considerably between the ages of 21 and 26. And then again, from 27 to 32. So much so that while I think my core values and beliefs have remained the same most of all my adult life, there are aspects of that person all those years ago I don’t recognise.

"Such as the terrible need I once had to fit in, be accepted and loved. When I was 18 and while making Pep Squad it occurred to me (wrongly) that if I were famous and rich, that people would love me and that would make me happy. Truthfully, all I needed to do was figure out how to love myself and build my inner self. Which is something I began to do during the process of trying to get Firecracker off the ground. I'm not sure I'd have been able to create Firecracker had I not been in that exact moment in life. Adolescence was dead, I was an adult, but not really (I don't think anyone should really be mentally and emotionally considered an adult until one turns at least 40). I'd also just met the person I was prepared to spend the rest of my life with. More on that in a minute. (Laughs again)."

How do you feel when you look back at the massive complexity and ambition of Firecracker, given how contained your later films tend to be?

"While the scope of Firecracker was massive on a crew-to-cast ratio, I haven’t felt any of my movies being simpler to make. And in the case with Casserole Club, I’d say it was more challenging thanFirecracker in a lot of ways. I think that what I learned most while making Firecracker was that one didn't need a separate person to do a single job, but that it was more efficient to have one person handle several jobs – thus cutting down on the size of the crew and keeping costs lower."

Your self-distribution of Firecracker (as documented in Wamego Part II) was innovative and radical - maybe even a bit maverick - nine years ago but in today’s world of multiple distribution channels, any film-maker can be their own independent distributor. Rather than you adapting or compromising, it’s like the industry has actually come to you. How do you feel about that?

"I love it. I don’t know how many people out there are aware of what we did back then. I mean, it was before Facebook. Before social media of any sort. We still had to fax press releases. I often wonder how it would be if that time were today. Would it have been wildly successful, or would we have been lost in the dust? Back then nobody was doing something like that, so we stood out and got a lot of attention because it was unique."

To what extent were the Wamego trilogy intended to document and/or inform, and to what extent were they your own catharsis in response to the shit you went through around Firecracker?

"My objective all along was to help document our journey – struggles and all. When I started out there wasn't a map to follow, or hidden secrets shared by other filmmakers. It was rare to find any real information, so I decided to share it with the world, no holds barred. Even when there are moments of failure, or success, it was important for me emotionally to never shy away from them. I'm so very thankful I did that. I've actually heard from quite a few filmmakers throughout the years since how much they appreciated learning about my journey and how it helped shape theirs."

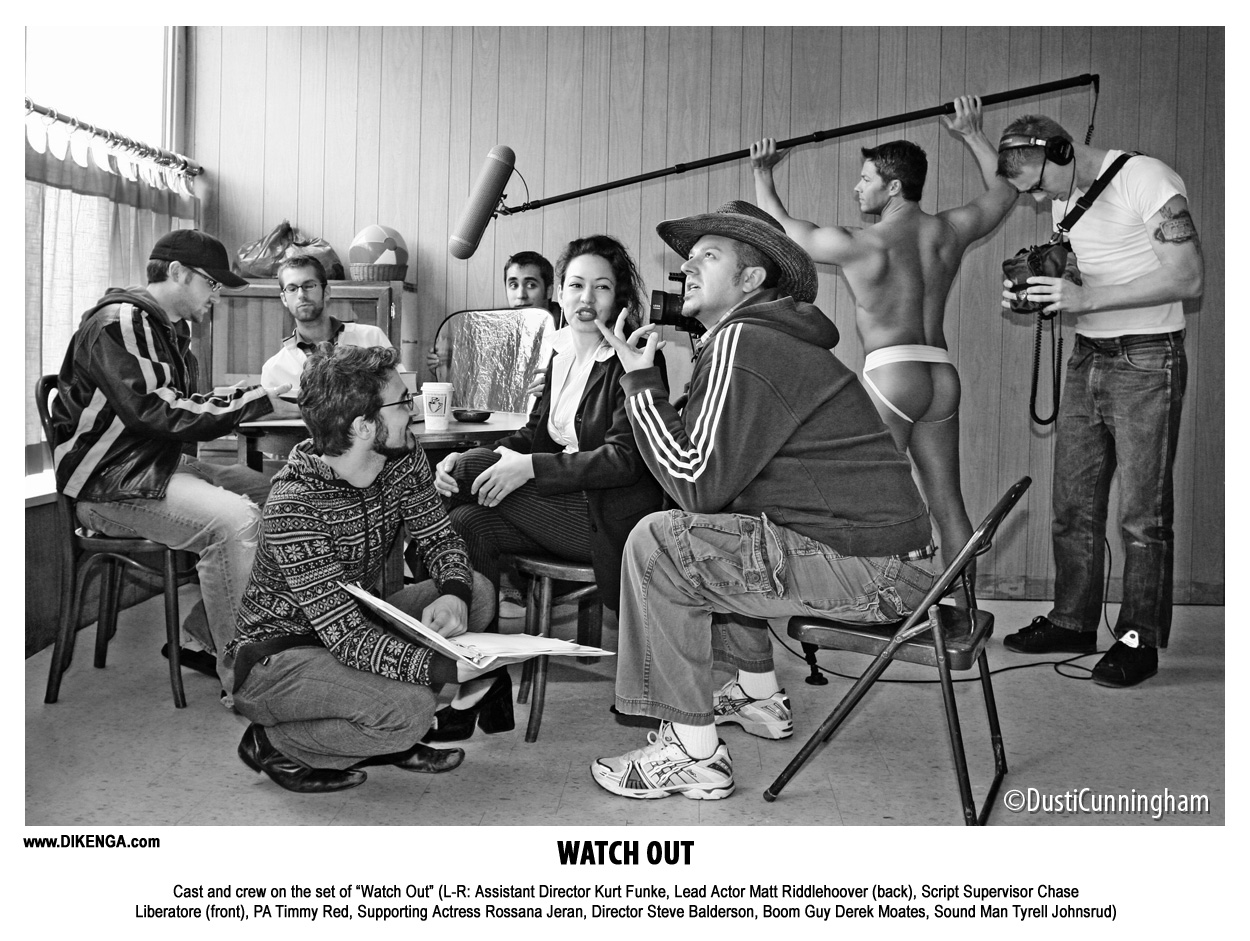

Watch Out is probably your most extreme film: how much leeway or restraint did you exercise in terms of potential (or actual) ‘shock value’?

"Well, I’m not one to normally like shock value for the sake of shock value. While I love John Waters’ movies, my studies came from learning Hitchcock – a master of showing as little as possible to gain the maximum impact. In the book Watch Out, the descriptions were so vividly described, it was nearly vomit inducing in some parts. I also learned a lot about sound while making Watch Out. Paul Ottosson, who won the Sound Design Oscar for Hurt Locker and nominated for numerous other movies, did the sound with me. In the scene where he's cutting off the pop star's toes, it's the sound that makes it extreme. You really only see a bloody toe and foot in two shots that each last for less than 24 frames. And, of course there's the masturbation scene. The moment of ejaculation needed to pass by so quickly the viewer could miss it if they blinked, and then wonder: 'Did I just see what I thought I saw?' I think showing that kind of subtle restraint when working in extreme matters is more effective than simply being gratuitous."

Your films often have distinctive colour palettes, so why did you choose to shoot Stuck! in black and white?

"I really wanted to give it that film noir feel of the women in prison films from the 1950s. Caged and I Want to Live were my inspirations. I wasn't all that interested or inspired by the exploitation women in prison films of the '70s."

By the time you made The Casserole Club you had developed an incredibly efficient and simple filming strategy. How did the way you and your cast and crew worked on set affect what audiences saw on screen?

"By creating an environment that is fun and enjoyable, the chemistry that actually exists in real life is easily passed through the characters on screen. Casting that film was tricky, in that it was important not only that the person be right for the part, but also that they had the right personality to balance the overall group when the cameras weren't rolling. We lived together in two vacation rentals in the same neighbourhood, really making the environment like summer camp. I developed a manifesto for the process and made everyone read it. By getting everyone on the same page from the get-go there were no surprises. People knew what was in store for them. And the people who couldn't handle the manifesto weren't considered to be on the cast or crew. One person lied on the manifesto (my assistant) and was fired on the third or fourth day. From that moment on, I've always respected the purpose of the manifesto and use it still."

Your next two features – Culture Shock and The Far Flung Star – were lightweight, ‘fun’ movies which seemed like a reaction against (and release from) the intensity of your previous films. Is that a fair judgement?

"Absolutely. Casserole Club took a lot out of me emotionally. In hind-sight, I was probably picking up psychically on my ex’s betrayal (which at that point was in full effect unbeknownst to me); so the messages I had about relationships and marriage were really deep and sometimes very painful and personal. I deliberately wanted to do something light, and without meaning. You know, several people mentioned that Culture Shock and Far Flung Star weren't real Balderson films, because when the audiences finished watching there was nothing to talk about. Sure they were fun, and entertaining, but most people missed the inevitable conversations that come from my movies. They wanted to dissect the characters and really analyse the story—but there was nothing to discuss. Which is, at the time, what I needed emotionally and creatively. I wanted to make something frivolous and just, well, entertaining. Eye candy for the sake of nothing more than eye candy."

It’s 15 months now since you sent me the screener of Occupying Ed. Why has it taken so long for this wonderful film to be seen by other people?

"Well, to pick up from my early story… Just weeks before I was to direct Occupying Ed, I discovered my partner (of 13 years) had hidden his tax returns for the previous 10 years or so, and for whatever stupid reason, had forgotten to take them with him when he abandoned me a couple weeks prior. So I Xeroxed all the records and bank statements, and in doing so, I discovered he betrayed me, having conned me out of about $250,000. It was devastating. My friends and family now refer to him lovingly as 'Bernie Madoff.' (Laughing).

"I’ll tell you, one of the hardest things in the world to do is produce and direct a romantic comedy-drama after being blind-sided by your husband who turns out to be a sociopath. My job was to direct a film about love in the middle of feeling total despair. I’ll also tell you – the film might have just saved my life. With friends and a good solid support group around me, I was able to make it through Occupying Ed without too many breakdowns. There are some amazingly tender scenes in that movie, which I poured a lot of my soul into. And the two songs by Samuel Robertson, 'Continents Were Made to Sink' and 'I am Your Planet' were songs I'd listened to repeatedly with Bernie back when I believed his affection was real. I'm so thankful for Samuel allowing me the rights to license those songs for the film. Even though I didn't write Occupying Ed (Jim Lair Beard wrote the screenplay), it became so personal to me that I felt every word, and saw every frame of film, in the roots of my soul. It was incredibly healing to actually make the film.

"But, it took a long time to finish. And in the months since I sent it to you for review, we've been trying to get it screened publicly. Yet, very few film festivals have had the courage to program it. Not because it’s too unusual, but my hunch is that it’s because romantic comedies are so cliché that many people avoid them, or somehow can’t take them seriously. Which makes some sense to me. It's rare that any film festival or high-art establishment screens romantic comedies. But, with the support of many festivals in Europe, we finally begin our festival run with the premiere at Raindance in London on 29 September."

Do your belly-dance documentary Underbelly and your avant-garde feature Phone Sex fit neatly into your cinematic career or should they be seen as experimental anomalies?

Do your belly-dance documentary Underbelly and your avant-garde feature Phone Sex fit neatly into your cinematic career or should they be seen as experimental anomalies?"Oh, I think they’re a different thing altogether. Phone Sex for one was originally conceived as a video installation for an art gallery. The 'premiere' was actually had at a gallery, where it became interactive with the people who came to the opening. I treated it as an art opening, rather than premiere. Underbelly was a great exercise in being a journalist. I felt that perhaps I was a secret television station out to do an expose on this amazing world of burlesque, comedians, belly dance and the amazing women and men who inhabit that world. I’d definitely do another documentary in the future, but it's a lot to invest in two years of your life… So it would have to mean a great deal to me."

Several of your films have premiered in London. Why do you think your small-town-in-Kansas approach to films chimes with British audiences?

"I have no idea, but I love it. I think it’s also hysterical that if I have a screening in London it sells out, the entire room is packed with fans and interested moviegoers. Whereas, if I hold a screening in Kansas City, hardly anyone comes. (Laughing again). Seriously. When I screened Casserole Club in Kansas City there were about 12 people there. Yet, when we screened it in LA we packed the 1,000-seat Egyptian Theatre on Hollywood Boulevard. And in London it was sold out as well. I don't know why but maybe my sense of humour is inherently British? My ancestors are from northern England after all. Or, perhaps it's the exoticness of the worlds I've shown on camera. The Kansas prairie, the Palm Springs desert mad-men style era, or the carnivals and old-timey Americana. Who knows. But I love it."

The Big Question: looking back at your own filmography, what do you think defines a Steve Balderson film?

"Well, like I mentioned earlier, I think one ingredient is definitely that after viewing the film can be debated with, discussed and examined more closely. For hidden meanings, metaphors, and that sort. But, I'd also say that my films are a bit autobiography. In the sense that they are about the very thing that is most interesting to me at the time. Usually when I decide to make a movie, it is the subject that I want to learn more about. I love learning about new things. Like, most recently, melodrama and killing people."

Finally, what’s the latest news on Hell Town and what else have you got cooking?

"Hell Town is one of my greatest. Of course, I share the writing and directing credit with filmmaker Elizabeth Spear. But, she and I have such a similar since of sick and dark humour that you won’t be able to tell what came from me and what came from her. Imagine Pep Squad on steroids. That’s Hell Town. I’m so in love with it. We've currently locked the picture edit. So now that the edit is done, we can begin sound design and music. I've worked with Mark Booker as an actor several times, but he's also an amazing musician and sound editor. He's currently working on Hell Town. I hope to have the color timing complete end of November, and then it's off to film festivals and midnight screenings. I'm so excited for everyone to become a hellion.

"Recently, I went to Los Cabos, Mexico, to direct another feature with Susan Traylor. That one, called El Ganzo, is still in the editing stage. It’s a mysterious memory remembered like a dream. It feels like my finest film. It co-stars Anslem Richardson and is set entirely in the Los Cabos region of Mexico – which was recently decimated by hurricane Odile. Please share this for support: www.cabohurricanefund.com

website: www.dikenga.com

No comments:

Post a Comment