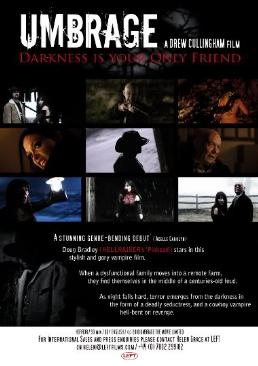

Writer: Drew Cullingham

Producers: Drew Cullingham, Charlie Falconer

Cast: Doug Bradley, Rita Ramnani, Jonnie Hurn

Country: UK

Year of release: 2011

Reviewed from: screener (Left Films)

‘Umbrage’ is a great word, isn’t it? It stems from the Latin ‘umbra’ meaning ‘shadow’, from whence we also derive such brilliant words as ‘penumbra’, ‘adumbrate’ and, of course, ‘umbrella.’ Its only previous significant artistic use that I know of was ‘Takin’ Umbrage’ by The Federation, a 1988 comedy single which spoofed The Archers.

Now here comes Umbrage: The First Vampire; no relation to Blood: The Last Vampire and the vampire here isn’t called Umbrage, although there is some talk of shadows. It was shot as just Umbrage.

First: confession time. I was really looking forward to watching Umbrage, which has a cool-looking trailer and some reliable people in front of and behind the camera. But despite my best efforts to enjoy the film, I found it disappointing, frustrating and ultimately unsatisfying. Which is a real shame, because it’s trying to do something different and in many respects does it well.

It is, for example, a good-looking movie. Any time I see James Friend’s name in the credits I know I’m in for a visual treat. For my money, he’s one of the best cinematographers working in British indie films. The production design by Charlie Falconer is also good and Scott Orr (The Zombie Diaries) provides a small number of decent gore effects.

Where the film falls down, as so often, is in the script. Drew Cullingham was writer, director, producer (with Falconer) and editor. When a single individual has that much input into a film, there’s potential for a pure, unsullied, personal vision to shine through - but there’s equal potential for major problems to be glossed over or ignored.

The threat here is ill-defined, and that’s a serious problem in a horror movie. It’s never clear what sort of danger our characters are in or why, so it’s difficult to feel any tension or indeed empathy. The threat is vampiric, but the vampire’s motivation is not clear and, in fact, that’s the greater problem right there. None of the characters have a clear motivation for their actions and as a result their actions don’t make sense.

Everything that every character does in a film has to be for a reason. It has to serve a purpose. Actually two purposes. It has to serve a narrative purpose, either progressing the plot or revealing the character (or both) but it must also serve a purpose within the reality of the story. It has to be exactly the sort of thing which that character would do in that situation. And if it’s strange or odd or unlikely or very different to what most people would do in a similar situation, then that difference must be justified and explained, whether at the time or retrospectively.

For example, imagine that you are a husband with a heavily pregnant wife expecting your first child. Would you, only days before the baby is due, in the middle of winter, move into an isolated 17th century farmhouse 20 miles from the nearest town which has no telephone connection and no mobile signal?

Or perhaps you’re going camping in the woods with your mate. (Actually, does anyone outside of horror films realy go camping in the woods? Everyone I’ve ever known who likes camping pitches their tent in fields, or maybe on moorland, or maybe (if they’ve got any sense) on a campsite. Or if they’ve really got sense, they stay in a hotel. But who camps in a wood?)

Anyway, you and your mate have pitched your tent amid the trees and necked a bottle or two of wine when a softly-spoken, attractive young woman appears, not wearing any sort of outdoor gear, claiming to be a birdwatcher looking for owls. After a few minutes, she leads your horny friend off into the darkness and shortly afterwards you hear him scream in terror. You find him, trouserless, face and crotch both full of blood, his dismembered member a few feet away. The girl, who is calm and bloodless and gives every impression of being on drugs, tells you that “the shadows came alive.”

Would you leave your critically injured mate there to die, not even bothering to offer him any comfort, and leg it through the trees with the apparently stoned girl? Really? Why would you do that when the most likely explanation is that your friend was attacked by either her or an accomplice?

Now go back to pretending you’re the expectant father. In the middle of the night, two strangers bang on your farmhouse door. One is in a panic and has obviously been drinking heavily, the other appears to be blissed out. The panicky one reckons that the silent, smily one told him that “the shadows came alive” and that’s why you must let them in because they’re in terrible danger.

I realise that you, in this role-play, cannot call the cops because you have no phone (though you do at least own a shotgun). Nevertheless, would you just invite this drunkard and his junkie girlfriend into your house to sit down next to your already stressed, heavily pregnant wife?

Do you see what I’m getting at here? One more for good luck. Our dad-to-be (played, did I mention, by Doug Bradley) is an antiques dealer and he has come into possession, somehow, of a large Babylonian obsidian mirror (obsidian is a kind of black, volcanic glass). I’m not sure the Babylonians made mirrors from obsidian (though the Aztecs did). Anyway, this thing is absolutely priceless, the oldest known example, in perfect condition - so why would you have it delivered by courier to an uninhabited farmhouse with instructions to just leave it in the barn? And why, having taken it out of its rather rudimentary packaging, would you be careful to remove the cardboard and paper from the barn but leave this 5,000-year-old, irreplaceable artefact propped up on a hay-bale where it could easily get scratched, knocked or broken?

All of these actions (and others) serve a purpose in progressing the plot but serve no purpose within the reality of the film. Time after time, characters behave in a way which is illogical, inexplicable or just downright nonsensical - but expedient. These are all the sorts of problems which should have been sorted out before the film got anywhere near even pre-production. This is why you do multiple drafts of scripts. And at every stage, the writer (or the director or producer - except here they’re all the same guy) should ask the questions that viewers and reviewers will ask. Why is he doing that? Why did she go there? What is the reason behind this decision that nobody in their right mind would make?

Let me give you a practical example, to prove that I’m not just blowing smoke rings here. I was recently doing some writing-for-hire on a script about a Victorian dentist whose schtick is that he makes the best dentures in London. He manufactures false teeth that are better and more realistic than even the finest porcelain, so that none of his competitors can work out how he does it. The dentist’s secret is that he steals teeth from orphans (the rotter!) and then has them polished to perfection by a colony of captive tooth fairies (the swine!).

All well and good, but if I was reviewing a film like that I would ask three pertinent questions (as, I’m sure, would you). (1) Why don’t the other dentists just assume that these perfect false teeth are made from real teeth? That’s kind of the obvious explanation, isn’t it? (2) How would this work, given that children’s teeth are significantly smaller than adult teeth? And would get even smaller if you polished them? (3) Why does he need the tooth fairies? Any fool with a magnifying glass can polish a tooth.

All well and good, but if I was reviewing a film like that I would ask three pertinent questions (as, I’m sure, would you). (1) Why don’t the other dentists just assume that these perfect false teeth are made from real teeth? That’s kind of the obvious explanation, isn’t it? (2) How would this work, given that children’s teeth are significantly smaller than adult teeth? And would get even smaller if you polished them? (3) Why does he need the tooth fairies? Any fool with a magnifying glass can polish a tooth.One Sunday morning I was lying in bed, turning things over in my mind, and came up with the following.

The only way to make false adult teeth from children’s teeth is to use three or four child teeth for each adult one, carefully cut and shaped into perfect building blocks. Such precision dental engineering, and the polishing of cracks between blocks to the point of invisibility, is the sort of thing that would be virtually impossible for even the most careful person - but not for tooth fairies. And because small children’s milk teeth have a different structure and slightly different chemical composition to adult teeth, when the other dentists examine these gnashers they can see that they are plainly not just polished human teeth, but they can’t work out what they are.

All three problems solved in one fell swoop. If that film gets made (and if they use anything from my draft) we won’t have audiences asking those three obvious questions.

So, Umbrage-makers, this is what should have been done here. A coherent, credible reason needed to be found for the antiques dealer to cut his family off from civilisation just before the baby is due; for the camper to abandon his gruesomely injured, dying friend without so much as a backwards glance; for the obsidian mirror to be in the barn; and all the rest of the script’s improbable unlikelihoods.

Jacob (Bradley) and his wife Lauren (Grace Vallorani: The Last Seven) are accompanied by Rachel (Rita Ramnani: Jack Says, Just for the Record, Strippers vs Werewolves), his resentful 18-year-old goth stepdaughter from a previous marriage which ended with Rachel’s mother’s suicide just a year ago. So crikey, he wasted no time, did he? Jacob and Rachel share a secret which, when we learn it towards the end of the film, actually shows that they are both terrible people, but at about the same time their characters clumsily change, especially Rachel’s, so that we are apparently supposed to like them and empathise with them even more.

Camping pals Stanley (James Fisher: Hellbride, The Devil’s Music) and Travis (Scott Thomas, also in The Devil’s Music) would seem to be significant among this small cast and we spend quite a lot of time with them but, in retrospect, it can be seen that they are entirely irrelevant to the actual plot. There is no indication of why the girl Lilith (Natalie Celino, who was in unreleased 2008 action-horror pic Furor: Rage of the Innocent) kills Travis, nor of why she doesn’t kill Stanley.

Lilith is, of course, a vampire. She’s actually the mother of all vampires, the woman who, according to some ancient Jewish legends, was Adam’s first wife before Eve was created from one of his ribs, who was later seduced by the archangel Sammael, an analog of Satan. A prologue set in the old west has tall, fit cowboy Phelan (Jonnie Hurn, who was the wheelchair-bound stepfather in Penetration Angst and also in both Zombie Diaries pictures) hunting down stout cowboy Sammaelson (AJ Williams or, as the IMDB has it, Aj Williams) but being attacked by Lilith who bites a chunk from his neck. This, I suppose, is how he becomes The First Vampire.

Lilith is, of course, a vampire. She’s actually the mother of all vampires, the woman who, according to some ancient Jewish legends, was Adam’s first wife before Eve was created from one of his ribs, who was later seduced by the archangel Sammael, an analog of Satan. A prologue set in the old west has tall, fit cowboy Phelan (Jonnie Hurn, who was the wheelchair-bound stepfather in Penetration Angst and also in both Zombie Diaries pictures) hunting down stout cowboy Sammaelson (AJ Williams or, as the IMDB has it, Aj Williams) but being attacked by Lilith who bites a chunk from his neck. This, I suppose, is how he becomes The First Vampire.Sammaelson is, therefore, either the devil or the son of the devil, but this sort of thing can only be gleaned from the Making Of, not the feature itself, where it is explained by ‘AJ Williams’ under his real name of Drew Cullingham.

This prologue and a subsequent, largely incomprehensible flashback, were shot on 35mm in the fake western town of Laredo, Kent, which I think is where a certain 3D comedy horror western musical was filmed. Everything else was shot on the Red camera. Thing is, the 35mm wild west scenes have then been tinted sepia, thus completely negating James Friend’s cinematographic skills. What’s the point of that?

Phelan turns up in Jacob’s barn 120 years later, still wearing a stetson but otherwise dressed in 21st century cowboy casual. He has been searching for Lilith all that time to take his revenge. I’m not sure what part the obsidian mirror plays in all this but at the end the two supernatural beings somehow disappear into the stygian reflector and reappear in Chiselhurst Caves.

Just in case we weren’t sure that this is the quasi-Biblical Lilith, there is also a flashback to, good grief, the Garden of Eden. Wait, is this a creationist horror film? Lilith is naked and so is Adam (Jason Croot, writer-director of horror mockumentary Le Fear) who is portrayed as a sort of Cro-Magnon caveman so maybe it’s not creationist after all.

NB. All my knowledge of Lilith was gained from her entry in Wikipedia and it’s quite possible that this was where Cullingham did his research too, as her appearance in the caves is obviously modelled on the 1892 John Collier painting at the top of her Wiki-page (complete with very large, very real snake draped around Ms Ramnani’s curvaceous, naked frame).

As for the shadows, I’m really not sure what’s going on there. At one point Stanley and Rachel are both attacked, quite savagely, by something invisible while they’re outside but Lilith sits placidly indoors. What are these ‘shadows’? What connection do they have to Lilith? And why did anyone think it would be scary in any way to have characters attacked by invisible things in the dark?

Umbrage is a mishmash of ideas that hasn’t been properly worked out. I’m all for horror westerns: Cowboys and Zombies was terrific. I’ve nothing against British westerns, not that’s there’s many to choose from. But trying to combine vampirism with the wild west and ancient Talmadic myths, all in a contemporary rural setting, centred on a dysfunctional family is a step too far, especially when there’s no real thought given to coherent motivation for any of the characters.

I feel a bit bad knocking the film like this because clearly Cullingham and his cast and crew worked very hard. The Making Of reveals a host of problems from malfunctioning generators on night shoots to Celino suffering an injury during a fight. A massive snow-fall halfway through production had to be incorporated into continuity and some of the shooting days lasted for more than 24 hours solid.

But this Making Of fails even more than the feature, skirting around what sounds like a real struggle against the odds to concentrate on amateurish shaky-cam interviews with clearly distracted cast and crew, of the sadly traditional “What are you doing now?”/”Can you describe your character?” type. Special sympathy for Scott Orr who graciously tries to answer the single most inane question ever included in a Making Of featurette: “So what’s it like being a Scottish special effects artist?”

Interwoven with these uninformative, uninteresting soundbites is a pretentiously black and white sit-down interview, post-completion, with Cullingham in what looks like a fancy restaurant or bar. While he is able to offer some insight into aspects of the film that don’t come across, he sounds smug, self-satisfied and complacent. Extraordinarily, the on-screen interviewer, ‘Making-of documentary director Ian Manson’, captions himself not just once but three times - in a film which is only about 20 minutes long! No offence, mate, but not only did we see the caption the first time, but also: we really don’t care.

Interwoven with these uninformative, uninteresting soundbites is a pretentiously black and white sit-down interview, post-completion, with Cullingham in what looks like a fancy restaurant or bar. While he is able to offer some insight into aspects of the film that don’t come across, he sounds smug, self-satisfied and complacent. Extraordinarily, the on-screen interviewer, ‘Making-of documentary director Ian Manson’, captions himself not just once but three times - in a film which is only about 20 minutes long! No offence, mate, but not only did we see the caption the first time, but also: we really don’t care.Given the troubles and travails of the production, this Making Of is a huge missed opportunity for a sort of low-rent Lost in La Mancha. Consider what Anthony Pedone managed with Camp Casserole despite the film under scrutiny running smoothly without a single problem, what could a really good director have made of The Making of Umbrage? In fact, this could have been one of those rare situations where a DVD is recommended on the basis of an okay film accompanied by excellent extras, But instead we just get 20 minutes of dad-can-I-borrow-the-camcorder interview clips with bored, tired cast and crew who have nothing to say, plus the black and white Ian Manson show.

I was disappointed with Umbrage because it wasn’t the film I was looking forward to, but I was really disappointed with the Making Of because it wasn’t the film it so obviously could have been. Also on the disc are a trailer, a music video (for the song in the trailer) and the full version of the Doug Bradley interview from the Making Of, in which he starts by patiently explaining that he’s best known for playing Pinhead in Hellraiser. Doug’s a pro and he’s used to this sort of thing by now. Since I last saw him on the set of Pumpkinhead 3, he has appeared in (or provided a voice for) a range of UK and US features including The Cottage, Ten Dead Men, Jack Falls, The Infliction and most recently The Reverend.

Mention should be made of the Umbrage soundtrack which features a range of interesting ‘new country’ tracks that give the film a very unusual feel. In many ways, the music is the best part: strikingly original, well-chosen, integrated with the action but never dominating. And often toe-tappingly good - yeeha! The actual music credit is ‘Captain Bliss and Huskie Jack’, two musos who have, very impressively, toured as part of John Mayall’s band!

On the aural downside, whenever character voices are distorted in spooky, demonic ways, they become nigh on impossible to understand. Victoria Broom (Zombie Women of Satan, Dead Cert, Forest of the Damned 2) is credited with ‘special FX voices’.

James Friend’s other recent credits include Stalker, Dead Cert, Jack Falls and Ghosted. Scott Orr worked on Evil Aliens and A Day of Violence while make-up artist Pippa Woods has a CV that includes The Reeds, Stalker, Doghouse and Elfie Hopkins. Cullingham and Falconer have also worked (as DP/co-writer and production designer) on Tim Biddiscombe’s thriller NightDragon (also with Fisher and Thomas in the cast). A significant number of the cast and crew worked on The Zombie Diaries or its sequel and that film’s Michael Bartlett gets a curious credit here as ‘guest director’.

If you want a British vampire western, this is probably the best you can pick. Doug Bradley buckles down to his usual reliable performance, some of the other acting is also good (some less so) and there are some clever moments. But Umbrage - which was retitled A Vampire's Tale in the States - could have been so much better and its problems stem not from any unexpected snowfall or malfunctioning generator but from a poor script which was nowhere near ready to shoot.

MJS rating: C+

Review originally posted 17th September 2011

No comments:

Post a Comment