Producer: Steve Balderson

Cast: Pleasant Gehman

Country: USA

Year of release: 2007

Reviewed from: screener disc

Website: www.dikenga.com

[Please bear in mind when reading this review that it is based on an incomplete advance copy of the film. - MJS]

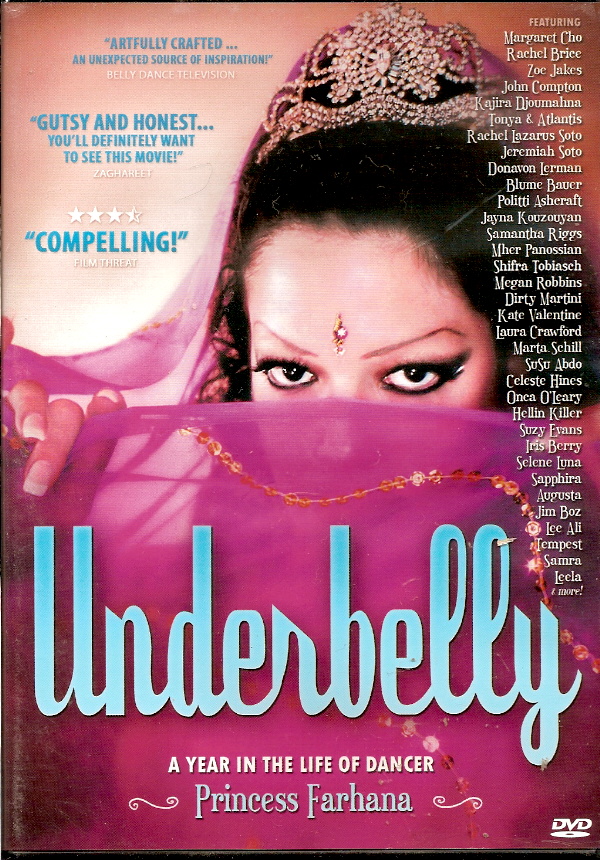

Steve Balderson has made five feature films and I have loved every one of them. Two dramatic features – the blackly comic Pep Squad and the achingly beautiful Firecracker; two extraordinary documentaries – Wamego and Wamego Strikes Back; and one fascinating avant-garde film – Phone Sex. At the end of October 2007 Steve was honoured with a three-night mini-season of his work in New York, which Film Threat called “the most deserved tribute of all time”. The day after the last NY screening, I received a screener disc of Steve’s sixth feature, his belly-dancing documentary Underbelly. I couldn’t wait to see what he had come up with.

I have always strived for honesty in these reviews and that’s why it breaks my heart to say that I was disappointed with Underbelly. Not just a bit, but really very disappointed. It’s not that it’s a bad film, it’s not that it’s dull. No, Underbelly commits a sin greater than either of these. It’s ordinary.

This is, in a nutshell, 100 minutes of talking heads and documentary footage about the world of belly-dancing and specifically a dancer/teacher named Princess Farhana, aka Steve’s friend Pleasant Gehman. And that’s all it is. It’s a Steve Balderson film and there should be something more, but there isn’t. None of Steve’s first five films could be put into a nutshell, not even something as simple in its premise as Phone Sex. But I could stop this review now and you’ll have learned everything you need to know about Underbelly. It’s not, to coin a phrase, Balderson-esque. Frankly, this could have been made by anyone. And that’s got to disappoint any film fan who has started exploring the director’s oeuvre.

There are other problems with the film, not least that it doesn’t know whether it’s a documentary about belly-dancing or about Princess Farhana. It tries to be both and ends up being neither. We learn very little about Pleasant, other than that she had Hollywood parents and was involved in the punk scene (we don’t even know whether this was real, 1976-77, safety-pins-and-spit British punk or whether it was the late 1970s, CBGB’s New York punk scene). She comes across as a loud, friendly, confident, enjoyably filthy-minded party person who genuinely enjoys both performing and teaching. Most other interviewees seem more sedate although some of them are not as articulate as a documentary usually requires: too many ‘so yeah like’s and unfinished sentences. One or two people who speak to camera in the documentary scenes have the love-me-look-at-me-love-me desperation of the low-ranked, low self-esteem performer-wannabe which is actually perversely fascinating from a pop psychology point of view.

So if we learn comparatively little about Pleasant Gehman, what do we learn about belly-dancing? Again, the answer sadly is not much. There is virtually nothing on the history of the art-form, beyond a couple of observations that it has been around for a few thousand years, and nothing at all on how it has spread across the globe. The physics and anatomy of belly-dancing is fascinating: what sort of muscle control is required to ripple your belly like that and how can the head be held so balanced while the torso moves? In short: how do you do it? But that’s not touched upon. There’s nothing at all on the music or the costumes. One lady comments that she was dancing in a club during the period that the hostages were held in the American embassy in Tehran and that she was worried about people’s reaction and this could have prompted a potentially fascinating examination of how this facet of middle-eastern culture is regarded in 21st century America, given the current antipathy towards (and ignorance of) the Middle East in that country. But no, that’s not here either.

Probably the biggest omission is the audience. We see several shows of various sizes in unlikely venues ranging from an Iowa car dealership to a Northampton cattle market but the question is never asked, let alone answered: who watches belly-dancing, apart from other belly-dancers?

There is a lot of stuff about how empowering it all is and the confidence thing and women being happy with their bodies and suchlike but frankly a lot of the comments could be applied to all manner of female-dominated physical activities, from lapdancing to lacrosse. We are given no insight into what makes belly-dancing different, only what makes it good and special – and everything is good and special to those involved in it.

There are a few references to the different styles of belly-dancing but, frustratingly once more, we are told nothing about these different styles or their various cultural origins. From the neophyte’s viewpoint, it all looks the same, with a fairly limited repertoire of moves. Of course there’s a great deal to it and layers of complexity which could be peeled back, but any artistic form looks much of a muchness to someone with an outsider’s view. Someone who knows nothing about hip-hop probably couldn’t tell A Tribe Called Quest from 50 Cent; someone with no knowledge of classical music would have difficulty distinguishing between Vivaldi and Rimsky-Korsakov; to someone who can’t stand anime (such as myself), Miyazaki’s work seems no different from any of the rest of it. Do you see where I’m going with this? A feature-length documentary about belly-dancing is an opportunity (God knows they don’t exactly come along very often) for experts within the field to impart some knowledge, to enlighten the general public about the hidden complexities of what they do. But that doesn’t happen here.

I’m not suggesting that Steve should have tried to cover every aspect of the history, geography, sociology, politics and anatomy of belly-dancing in one film; it’s up to him as director to decide what to concentrate on and what approach to take. But a film like this needs to concentrate on something in order to justify the exclusion of areas about which the audience might be curious. Underbelly doesn’t concentrate on anything, as far as I can tell, but still excludes stuff, leaving the viewer not much wiser about belly-dancing – or indeed, about Pleasant Gehman - than he or she was before. There doesn’t seem to be a point to this film. What is it trying to say? All five of Steve’s previous films were very personal projects and this one clearly isn’t. It’s a film about his friend and her world and consequently there’s no real passion driving the work. It documents when it should explore and explain. Instead of a journey into the world of Princess Farhana, it’s just a bunch of talking heads and dance clips.

Surprisingly, the former outnumber the latter by a considerable margin. The one thing I would expect from a belly-dance documentary, whatever else it may strive to do, is plenty of footage of people belly-dancing. But we’re nearly half an hour in before we get the first decent look at a performance and even then it’s annoyingly short. We want movement and poise, we want beads and chiffon, we want shimmying and stepping. Where is the dancing? I’ve never seen a proper belly-dance performance – realistically, who has? – and it would help the film enormously to start off with an unedited, well-shot sequence of someone dancing, maybe combined with a few captions bringing us up to speed with the facts and figures of belly-dancing. How old is it? How popular is it? And so on.

The interviews themselves are shot in a low-budget style, with a single handheld or tripod-mounted camera, mostly by Steve himself although a second unit was used for the British footage. Sometimes the light is slightly too bright, sometimes the room is slightly too echoey, in places there is an almost guerrilla feel to the interviews but this is not reflected in the post-production which could have used this roughness for an effect of immediacy and in-your-face cinema verite. Instead these are just competently-but-prosaically edited-together talking heads with a little subtitle caption to introduce each person. Several of the interviews include cuts between sentences, where the soundtrack is continuous but the image jumps, and in most documentaries these would normally be covered up with a cutaway to a still or some other footage. In other words, this is exactly the sort of situation that requires more dancing footage. I can’t understand why Steve keeps showing us people sitting on sofas when we could be seeing them (or people like them) wiggling their stomachs to the sound of a funky tabla.

As for the interviewees, some of them are described on-screen as just ‘belly-dancer’ while others have either a website address or a note that they are the producer or organiser of something. The web thing, while it’s very 21st century, doesn’t actually tell us who these people are. Professional dancers? Teachers? Enthusiastic amateurs? And the events or organisations which we are told some people run are things that mean nothing. What is really needed, to give these people’s views some context, is a fuller caption at the start, maybe over some footage or stills of them dancing: “Nora Jenkins has been dancing for five years since her husband Bill died. She is a 46 year-old bus driver from Chicago.” Something like that. Because without really knowing who these people are, what their interests are, what their relevance is, what their experience is, their words don’t mean a great deal.

Probably the best interviewee isn’t a belly-dancer at all but the owner of a shop specialising in world music. In fact it is precisely his semi-outsider view, from the fringe of the belly-dancing world, that makes his thoughts and observations more interesting than all the women sitting on sofas saying that belly-dancing empowers them and Pleasant Gehman is a great lady.

The film is divided up into chapters with little title cards but only two of these sections show real promise. One is a part of the film discussing male belly-dancers; who even knew there was such a thing? Three are interviewed and shown dancing, and various female interviewees give their opinions on how male dancers differ from female ones. There is a tremendously trenchant observation that men tend to dance externally, presenting themselves to the audience, while women dance more internally, dancing for their own pleasure.

The other part with some spark in it deals with fusion belly-dancing and the contrasting views of the young radicals versus the purists. There are goth belly dancers, there are burlesque belly dancers. Gehman is shown doing a routine which starts in a clown outfit and finishes with her wearing nothing but a thong and pasties. This undoubtedly incorporates some belly-dancing moves but it’s basically a Lily St.Cyr-style striptease. Ironically, the movie starts off with belly-dancers vigourously defending the art-form because some people ignorantly assume, what with the skimpy costumes and pelvic gyrations and all, that it’s akin to stripping. But then, an hour later, when a belly-dancer actually does strip, no-one is challenged over this, which seems a missed opportunity. Nevertheless it’s interesting to hear belly-dancing purists condemning those people who (as they perceive it) learn a few moves and then start mixing the style with other dance forms. The danger is that belly-dancing in its pure, traditional form may die out.

The other part with some spark in it deals with fusion belly-dancing and the contrasting views of the young radicals versus the purists. There are goth belly dancers, there are burlesque belly dancers. Gehman is shown doing a routine which starts in a clown outfit and finishes with her wearing nothing but a thong and pasties. This undoubtedly incorporates some belly-dancing moves but it’s basically a Lily St.Cyr-style striptease. Ironically, the movie starts off with belly-dancers vigourously defending the art-form because some people ignorantly assume, what with the skimpy costumes and pelvic gyrations and all, that it’s akin to stripping. But then, an hour later, when a belly-dancer actually does strip, no-one is challenged over this, which seems a missed opportunity. Nevertheless it’s interesting to hear belly-dancing purists condemning those people who (as they perceive it) learn a few moves and then start mixing the style with other dance forms. The danger is that belly-dancing in its pure, traditional form may die out.There is actually a fairly lengthy sequence about burlesque which, while it’s evidently another of Gehman’s enthusiasms, sits oddly in what professes to be a belly-dancing film. Ironically, this was probably the part I enjoyed most and found most interesting although this may be a personal reaction because, while I know absolutely zip about belly-dancing, I do have a passing interest in burlesque. I’ve read a couple of books, seen a couple of Bettie Page movies, so I’m not starting from a position of complete ignorance like I am with the belly-dancing.

Anyway, here’s what all this boils down to, and it’s something which occurred to me about halfway through the film. Underbelly has been made - whether deliberately or accidentally - for people who are already involved in the American belly-dancing scene. If you know who these people are and you’ve seen their websites and you’ve been to their events, then this will all make sense to you. There is, for example, discussion and footage of some big annual bash called Tribal Fest but no attempt to explain what it is, the assumption being that we all know about Tribal Fest even if we’ve never been there, the same way that we all know about the Cannes Film Festival or the Olympic Games. Except that we don’t. All it needs is a caption or one person telling us, in a sentence or two, what’s going on here.

The Wamego documentaries didn’t assume that we all knew about producing and distributing films (and in any case, as films about the film business, their target audience naturally has some interest in the subject matter). Unless Steve is planning only to show Underbelly at belly-dance events, I fear that he has seriously misjudged his audience.

Off on a slight tangent now. The deepest, darkest reaches of Amazon.com contain some unexplored tributaries where specialist documentary DVDs lurk. Every interest has them, whether you’re into cross-stitch or car-repairing, budgie-breeding or turkey-hunting. They’re usually rough and ready, from the Dad-can-I-borrow-the-camcorder school of film-making, but they sell in small numbers to the faithful and nobody else ever sees them so that’s all right then. Belly-dancing probably has its own films like that (one of the interviewees refers to “DVDs - and not even my DVDs”) and I suspect that Steve Balderson has made a film which, while it’s undoubtedly better produced than most of these things, has the same lack of appeal to anyone outside of the world it documents.

Steve’s not a belly-dancer (at least, I don’t think he is!) but ironically it may be his absence from the film which condemns it. He stays silent behind the camera, all his questions carefully edited out. Perhaps if this was a film about Steve Balderson exploring the curious world of American belly-dancing, it might be more personal - a film-maker’s journey - and thereby not only more like Steve’s other films but also more interesting for the non-dancer. There’s no authorial voice here; that’s why it’s just a run-of-the-mill documentary, rather than a Steve Balderson documentary.

Just as a drama or comedy requires a central character with whom we can emphasise, so does a documentary. The reason why far future stories from The Sleeper Wakes to Futurama often have a present-day protagonist is because that person is us, the viewer, and as this strange new world is explained to the sleeper awoken, so it is explained to us. Well, special interest sections of society, largely off the cultural radar, are like the far future. It’s a world where the basic truths remain the same but the details and the context are beyond our understanding. Who are these people and why do they do what they do? What are the rules, the structures and the limitations of this world in which we find ourselves? We need someone freshly awoken, who is as new to this world as us, to ask the questions for us and, if necessary, translate the answers. A wandering camera can’t do that on its own.

We also need a plot, a quest, the film-maker’s journey as hero’s journey. The reason why documentary features like Roger and Me or Supersize Me (spot the connection?) worked is because they documented the film-maker on a mission. Probably the best comparison to Underbelly among successful documentary features (at least, the ones I’ve seen) would be Spellbound, which introduced its audiences to competitive spelling bees, a world as alien to most of us as professional belly-dancing. But Spellbound had a plot and characters, following several children and their families as they competed through the regional and national levels of that odd competition. Underbelly doesn’t seem to have a plot, or any characters apart from Pleasant Gehman, everyone else either wandering in and out of their own scenes or sitting on a sofa and chatting.

This is a picaresque documentary, a series of seemingly unconnected episodes. Here is Pleasant Gehman in Northampton, here she is in a car dealership, here she is on a cruise ship, here she is at Tribal Fest. There is no sense of progression or how any of these sequences relate to any of the others. At the end of the film - and this is, if anything, it’s most inexcusable flaw - neither Pleasant Gehman nor the viewer has changed in any noticeable way.

Finally, in what I depressingly note has turned out to be a barrage of criticism (although, I hope, constructive criticism) there are two points to make. First, I could not work out why (a) almost all of the footage of Gehman is in black and white while everything else is in colour, and (b) some of the Gehman footage actually is in colour. It’s a curious decision which has not been carried out one hundred per cent. Mainly, I just could not see the point of monochrome belly-dancing footage. Surely colour - the costumes and the skin tones - is part of the art-form’s appeal. The second point - and this is the quickest, simplest fix of all but stung me personally - is that a caption misspells the name of my home town of Leicester. Unforgivable!

So what is to be done? As explained at the top, this is not the finished version so there will be some changes. But, the spelling of provincial English cities aside, these will need to be more than cosmetic. There are fundamental problems with the selection and arrangement of the footage which makes up this film. Documentary-making is a curious art; there’s no script and no way for the film-maker to know in advance precisely where he is going to end up, although it helps to at least aim for somewhere as a finishing point, however much that may change during production. If Steve was aiming somewhere with Underbelly, he got diverted along the way and has ended up just wandering through the world of belly-dancing, without a clearly defined sense of purpose. His audience, inescapably drawn to travel with him, becomes frustrated when we realise that we’re not actually going anywhere specific, we’re just out for a leisurely stroll that will end up back where we started.

Somewhere on Steve’s shelves are rows and rows of tapes and/or discs, hours of footage from which Underbelly has been culled and constructed. I have no doubt that there is a terrific film somewhere on that shelf and I have absolutely no doubt that a film-maker as single-minded and undeniably talented as Steve Balderson can fashion that film in a way that no-one else could, surprising and delighting everyone who watches it.

But with Underbelly I think that Steve has sold himself short.

MJS rating: C+

review originally posted 2007

No comments:

Post a Comment